Our dog is our doctor

Willeford's memoirs cap a stunning, largely unknown legacy

Ringo stands on the threshold of our front door, nose in the air like Dr. Dolittle’s dog, Jip, standing on the bow of the Flounder and smelling the ocean breezes.

But I’m more chilled than impressed.

“In or out,” I say to him. “In or out, Ringo. All the cold air is coming in.”

Ringo doesn’t move. His amber eyes survey the lawn and the driveway and the road beyond. His ears stand up like a bat’s.

“Fine,” I say, giving up and walking away so the door drifts back against his legs.

His tail, which curves up over his back and turns left at the tip, twitches at the touch of the door. Moments later, he has vanished onto the lawn, patrolling the fence line, terrorizing squirrels and determining, somehow, whether each person who passes on the sidewalk will be wagged at, barked at or ignored.

Bella and I watch him out the windows of the library.

“He has yet to catch a squirrel,” I say, “which is a good thing. He has come close. But the squirrels are a little too fast for him. And maybe he isn’t quite sure what to do when he gets within striking distance. Probably he is, though. Probably, he’d snatch one right up if he could.”

“He’s a good dog,” Bella says.

“Yes he is,” I say.

All day long, he diverts us. He’s 4 now, fully grown but childlike in his eagerness to play and excitement to see us and other family members when we return to the house.

Who can suppress a smile when he struts around, wagging his whole body, bumping into our legs or sprinting up and down the hall, springing on and off the couch?

His unbounded pleasure at our presence always lifts my spirits and Bella’s, and they frequently need lifting. Boredom is our great affliction, brought on by Alzheimer’s, which has attacked Bella’s brain and made a lot of the diversions we used to enjoy hard or impossible.

We walk into downtown and around the block and to the coffee shop. We watch TV and fix meals and eat them. We make tea with honey in our metal cups with plastic covers, so it stays hot for hours.

When we’ve been watching TV too long, Ringo lets out a high-pitched yawn, stands up on the bed and shakes himself, jumps to the floor and stretches his back. If Bella and I are still in our chairs, he prowls the room, testing T-shirts and socks with his nose. He seizes one and walks it over to us, limp fabric drooping from his jaws.

“I think it’s time for a walk,” I say.

We’ve been going recently to Crandall Park in the afternoons, where Ringo can socialize with other dogs, also out for walks. He likes little ones. The larger ones, especially tough dogs like huskies, strike a protective chord. The ruff of his neck and a ridge of fur that snakes down his back stand up. A low growl rumbles out of him.

He’s strong and springy, but he’s only 65 pounds. I drag him away.

Children like his eyes and soft fur. He gazes into their faces and touches them with his nose.

Usually, wherever we are, his tail is wagging. When we walk, it points forward over his back and moves in the air like a rudder.

If he sees we’re returning to the car, and he’s not ready, he’ll balk and brace his legs. I pull, but his harness bunches up around his neck.

“OK,” I say, and drop the leash, and Bella and I walk to the car without him.

Immediately, he follows.

His devotion outweighs everything. I thought about saying he would follow us into hell, but that’s hyperbole. His survival instinct would take over, I hope, and Alzheimer’s isn’t hell, despite how it feels some days.

Readings

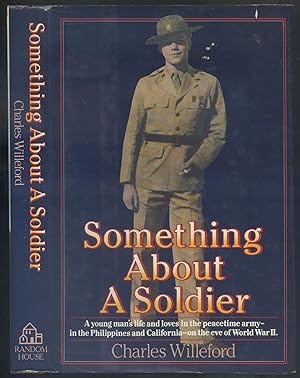

I read Charles Willeford’s “Something About a Soldier,” a memoir about his years as a teenager and young man with the U.S. military in the Philippines in the late 1930s. This book follows the memoir of his Depression-era childhood, “I Was Looking for a Street” — both of them written at the end of his life. He died in 1988, leaving behind a largely overlooked collection of memorable but hard to classify novels. Willeford’s style seems to be no style at all. His writing can feel dry. The stories are puzzling. Reading each of his books, I wondered why it was written and why I was reading it. But the stories have stuck with me long after other, more fluent and flowing novels have faded. Images from his books remain as sharp in my mind as if I saw them myself. It’s a shame Willeford didn’t hold on for a few more years, because I imagine he would have added a third volume to his memoirs, about his World War II experiences. But what is out there is jarring and special. His better-known books, like “Cockfighter” and “The Burnt Orange Heresy,” can be found for cheap online.

Subscriptions

It has been great to see a lot of people signing up for our newsletter, both with paid and unpaid subscriptions, since we began to offer the payment option last week. I see this newsletter as a sprout in the bedraggled orchard of journalism, and your support is water. Thank you!

You forgot to mention how good Ringo is at digging holes. He could have a career as a miner.

The unconditional love from our pets is so life affirming. Thank you for your thoughts on Alzheimer's and its effect on our lives. We often forget the enormous impact the disease has on caregivers. I'm grateful you're writing about it.