Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

There are some stories during the course of your life that stay with you.

Tim O'Brien's story was one of those.

But actually, it isn't really Tim O'Brien's story, it is his sister, Kathleen Tighe's story, and his father Bernard's story and the entire O'Brien clan after being devastated on 9/11 and how they had to go on and live their lives despite the loss of two fathers.

When I was putting together my first collection of columns in book form, I knew the O'Brien story had to be part of the collection.

I put it in the section called "Life and Death" because the events of 9/11 was without a doubt the most life and death experience I ever had in the newspaper business.

So as we remember the attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon from 23 years ago, I want you remember the O'Brien family and Kathleen Tighe and her family again.

Here is the story that I first wrote 10 years ago.

9/11 is now personal

September 19, 2014

Let's start at the end of the story.

The last day.

The day Tim O’Brien died.

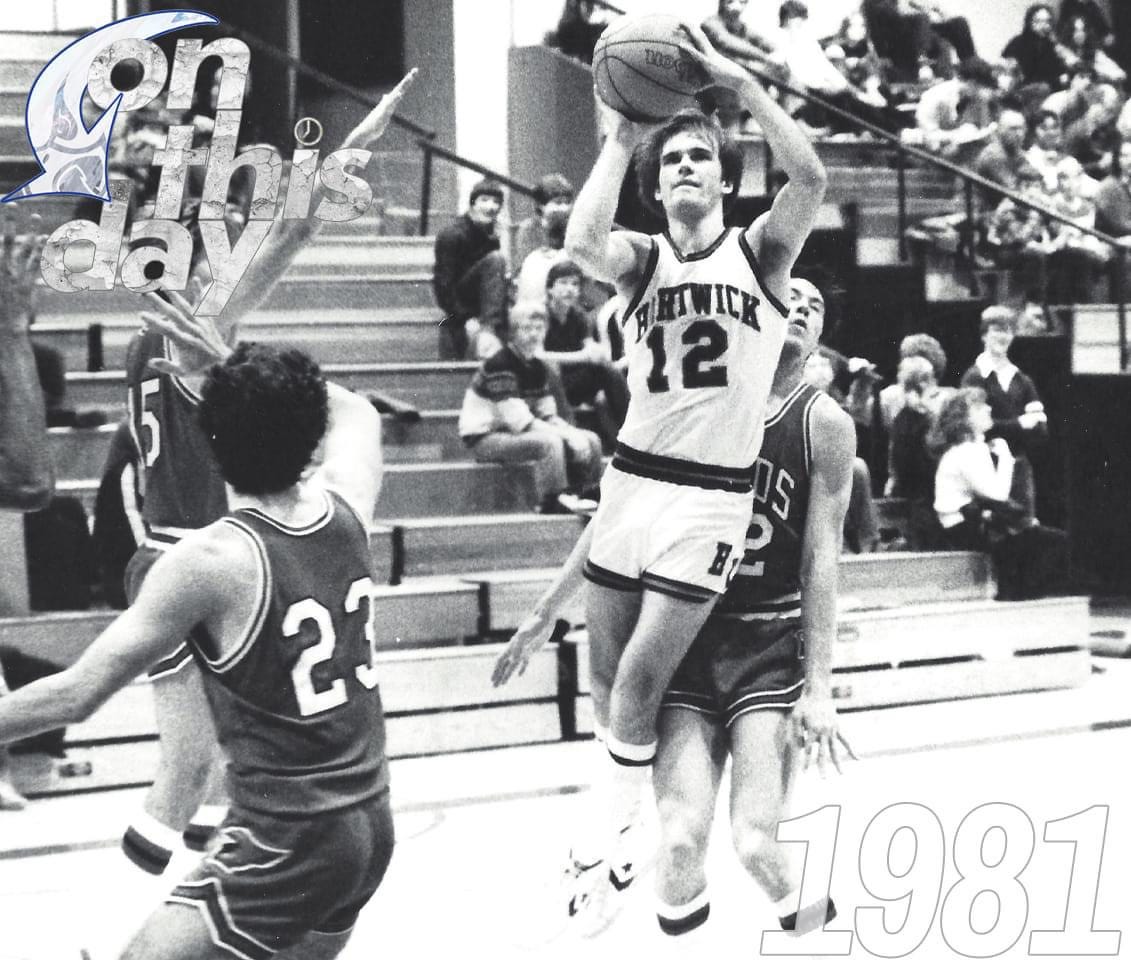

That’s what I had to do when I went looking for the name of a Hartwick College basketball star I last talked to 31 years ago. I just wondered how his life turned out.

He worked for Cantor Fitzgerald. You know the story now. He was only 40. He had a wife and three young children and was working on the 105th floor when the first plane hit. It was probably over quickly.

Let’s work back from there, because the end may be the least important thing about his life.

He lived on Long Island with his wife and three young children. His dad said he had his dream home with a putting green, tennis courts, pool and basketball court, and he was always out in the yard with the children. He was successful.

“He was the rock of the family,” his father, Bernard, said.

Think about that for a second.

How often does the father say that about the son?

“We couldn’t have asked for anything more,” Bernard told Newsday. “He looked after his family, he looked after his mom and dad, he did very well, he worked hard, but he didn’t forget his roots, and he was always there.”

O’Brien called his family “the fun family” and would lead the children into spur-of-the-moment mischief and leap into the the pool fully clothed, the children following in his wake.

“He taught me not to ever judge people or gossip,” his wife, Lisa, told Newsday.

Before moving to Cantor Fitzgerald in 1996, O’Brien worked at Patriot Securities on Wall Street.

His brother Sean told the New York Times in 2001 that when work intruded on his home life, he would tell a visitor, “ ‘Stay here.’ It just gave out a feeling of ‘I’m here and I’m going to come back to you.’ ”

Some people are like that.

One day in 1989, while working at R and J Securities on Wall Street, he interviewed a young woman for a job. It was Lisa.

“I didn’t hear a word he said,” Lisa O’Brien told Newsday. “I was just thinking, ‘OK, this is my husband.’ ”

And five years later they were married.

Lisa called him “Captain Catholic” because he regularly attended church and refused to curse. He sometimes would spell out the word he wanted to cuss.

His best friend was former New York Jets quarterback and current NFL television analyst Boomer Esiason.

O’Brien talked him into doing a charity golf tournament when Esiason was a second-round draft pick of the Bengals and O’Brien was just a year out of Hartwick.

“The friendship was born in the minute I met him,” Esiason told Cincinnati columnist Paul Daugherty.

Later, Esiason asked O’Brien to be one of the founding members for the Boomer Esiason Foundation, which raises money for cystic fibrosis research.

They played golf and basketball together. Their wives were friends.

When Esiason became quarterback of the Jets, O’Brien told him he would always root for him, unless he was playing the Giants. That was a deal breaker.

Nine days after 9/11, 3,000 people attended a memorial service in Rockville Centre, O’Brien’s hometown.

Esiason was one of four people to offer up a eulogy. He did it wearing a blue home jersey of the New York Giants.

“Only for my man, Timmy,” Esiason said. “Only for my man Timmy.”

There are people you meet in your life you do not forget.

I guess that’s why I wondered what happened to O’Brien, the All-American I had covered when we were both very young. I guess that’s why I searched for his name online.

And for the first time, the loss on 9/11 was personal.

I remember this poised, confident young man who could shoot the lights out from anywhere on the court.

His last game was in the first round of the Division III NCAA Tournament. Hartwick was the underdog against Potsdam State, but it battled all the way and trailed by just a point with seconds left.

And O’Brien had the ball.

He came down the court, was trapped along the sideline by two players and lost the ball.

I remember talking to him in the silent locker room. He was the only one talking. He kept saying over and over, “I just lost the handle on the ball,” and that he just wanted to have a chance to take that last shot.

Even now, 31 years later, I know he would have made it.

This past Thursday — on the 13th anniversary of 9/11 — Brian St. Leger, the center on that team, posted a photo on his Facebook page of a baby-faced, shaggy-haired young man holding aloft a trophy with a satisfied smile.

“September 11, 2001 — Always remember Hartwick great Tim O’Brien.”

More importantly, remember how he lived.

P.S.

When the 9/11 Memorial Plaza opened at Ground Zero, I found Tim’s name and ran my fingers across the etching as the water flowed into the footprint of the towers in front of me. Later, when I visited the 9/11 Museum in New York City, I listened to the interviews with his father and sister.

I didn’t really know Tim O’Brien that well, but it made the events of that day much more personal. I later heard from Tim O’Brien’s father and then a heart-wrenching email from his sister, Kathleen Tighe, that led to another column two years later.

Bernard O’Brien, Tim’s father, died in January 2020. He was 87.

The Last American Editor can be purchased at Ace Hardware, Chapman Musuem, Battenkill Books, McKernon Gallery, Fort William Henry, Lake George Steamboat Co. and The Silo.

Ken Tingley spent more than four decades working in small community newspapers in upstate New York. Since retirement in 2020 he has written three books and is currently adapting his second book "The Last American Newspaper" into a play. He currently lives in Queensbury, N.Y.

Thank you for this story on the anniversary. Thank you for your humanity and the telling, which amplifies the loss. But also the love and goodness. Appreciated.

Beautiful. Thanks for helping to keep the memory of 9/11 alive. Peace to all.