Please don't pretend there's anything good about Alzheimer's

Fascism describes our current condition

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

I wrote this last week, on a day I thought was Tuesday but discovered later was Monday.

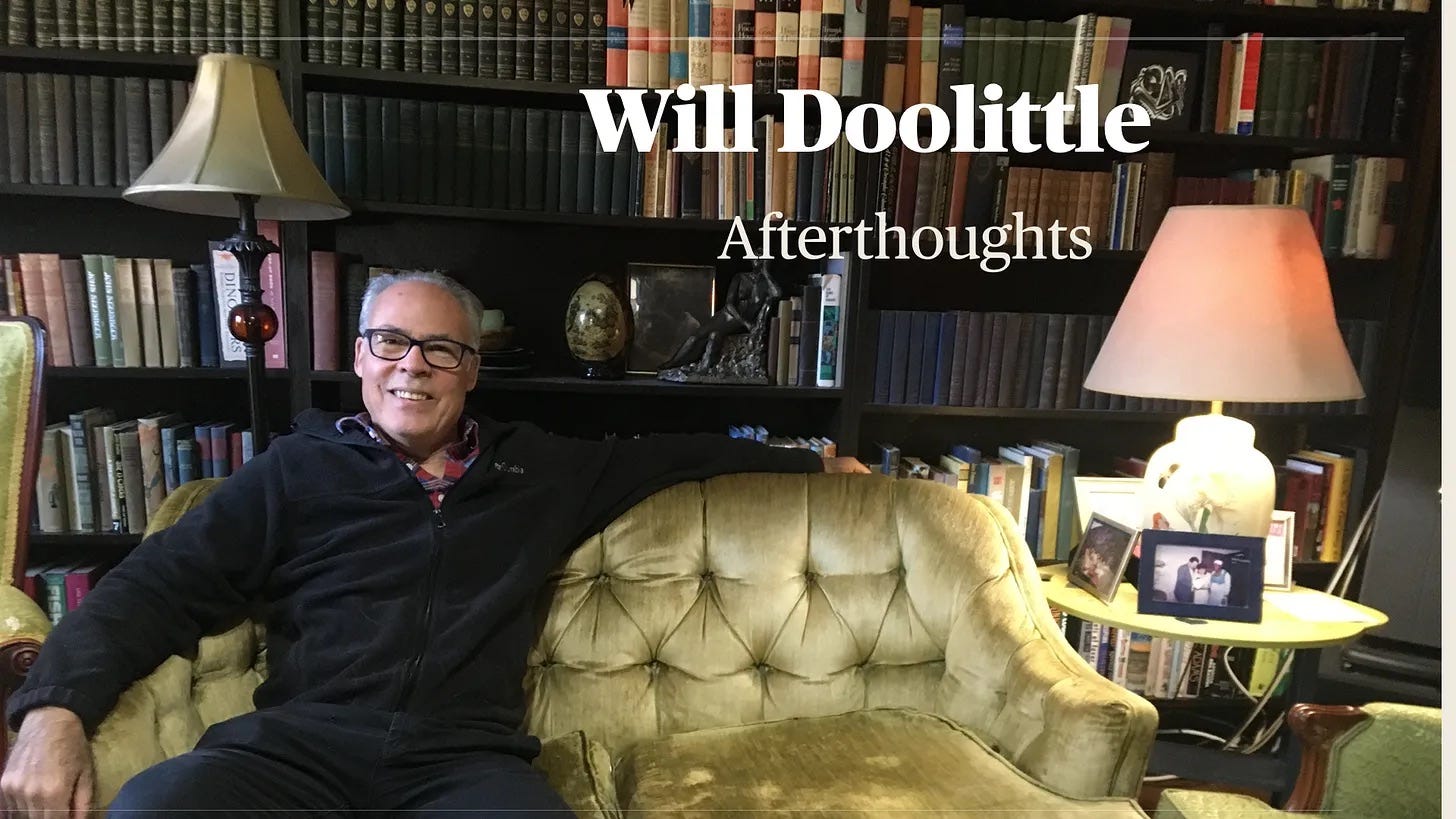

Mid-afternoon, I came downstairs after an hour or so in my office on the second floor to find Bella sitting in her underwear in a chair in our library.

She looked at me. I tried to act normally.

“Hi. Hi Sweetie. Do you want to put some clothes on? Come with me into the kitchen. I’m making something for us to eat. Then we can take it upstairs and finish watching that movie, OK?” I said.

She leaned against me when we got to the kitchen. Her skin was clammy, and she was panting.

“Do you want to pu—“ I started to say but felt overwhelmed by a sob. “To pu- pu-“ I stopped talking and took a breath.

Do you want to put your pants on?” I said.

“Yes,” she breathed.

The sob was unexpected. For years since Bella’s diagnosis with Alzheimer’s, I’ve been getting choked up over things that aren’t sad.

I’d try to read a newspaper story aloud to Bella about a great athletic performance, for example, and have to stop because my throat closed up.

Now I was sobbing over our actual circumstances, and it was a relief. At least it made sense.

I fetched one of the pairs of stretchy pants she wears and steered her toward a chair.

“Sit here, Sweetie, and I’ll put them on,” I said.

“Where?” she said.

“Here,” I pointed at the chair.

She took a step toward it.

“Sit down here?” she said.

“Yes, there. No, just sit … or I’ll put them on you standing up, that’s OK. Lift your foot, yes, good, now the other foot. Put this one down and lift the other one, this one. Yes. Yes. Pull them up,” I said.

I took a short-sleeved shirt from a drawer in her dresser.

“Here, we’ll put on this nice shirt, OK? I’m going to put it on you, OK?”

“What do I do?” she said.

“That’s good. Give me your hand, perfect. Now the other hand. Up a little bit. Yes. There. Better, hunh?”

“Thank you,” she said softly.

“Of course. That’s good, right? I’m going to make some dinner for us. Haddock and spring onions and baked potatoes, and we’ll take it upstairs and watch the rest of that Tom Cruise movie we were watching, OK?”

“OK. I love you,” she said.

“I love you, too, Sweetie.”

I had been upstairs by myself because Bella gets restless in the afternoon and wants to wander from room to room or sit in the library and stare into space.

If I pester her, she snaps, “Stop touching me!” or “I’m not a child!”

So I go upstairs for an hour or two.

Between 4 and 5 p.m., I give her her evening pills on a spoon with applesauce and a plate of food. Pizza is more popular than haddock.

We sit in easy chairs in the TV room, and she stares in the direction of the screen for 10 minutes or so until her eyes close and her mouth opens and her head falls to the side.

I wait for awhile, then walk her down to bed, clean up the kitchen and watch some more TV and do some calisthenics and read stuff on Facebook and do some writing.

We don’t talk much, but we can sit together quietly on the couch, sometimes for hours.

“Will?” she says.

“Yes Sweetie?” I say.

“I love you.”

“I love you, too.”

“I’m serious. I love you.”

“I’m serious too.”

She gives me a look, and I give her a kiss.

I’ve been reading the manuscript of a nonfiction book I’m critiquing for a writer I know, leaving the pages stacked on the coffee table in the library. But Bella keeps picking them up and shuffling them around when she wanders in there during the night or while I’m upstairs.

“I asked you not to touch these papers,” I said recently as I sorted through pages to put them back in order. “I mean —“

I mean what?

I mean, I know this is impossible for you to remember, but I’m insisting on it anyway?

I mean, I could stash the pages where you can’t get them, but I don’t want to?

I mean, I want to pretend I can be casual and normal in my own house, the way we used to be, even though everything has changed?

Bella tries to please me, which breaks my heart. She offers to help, even though she can’t. She apologized for half the day about the pages.

She sat for the whole Tom Cruise movie without understanding one scene.

It was called “Oblivion” and followed a couple of overlapping timelines and at least two Tom Cruise replicas.

Bella was asleep long before the end. She sleeps 11 or 12 hours a night and naps during the day, which helps me get things done around the house.

Caregiving is a daily struggle against disorder. If I can get our house and affairs into an ordered state, it compensates a little bit for her Alzheimer’s symptoms I cannot touch.

Now some people are suggesting it’s our attitude about the disease — our “tragic narrative” — that needs adjusting, and with a different outlook, we can find flecks of gold in the gravel of this experience.

I don’t know. I don’t think the people making those suggestions have spent eight years watching a loved one’s brain deteriorate a tiny bit more each day. I don’t think they have experienced the claustrophobia of being a sole caregiver or the aloneness that is worse than being alone, because the person who used to be your soulmate is there but unreachable.

It’s hard to see the bright side of Alzheimer’s. I’d give up all my attempts at order to make that one thing right.

Poem

Here is a poem from Hudson Falls poet Richard Carella:

The Flavor of Everything

If everything were forever... everything wouldn't

lose its flavor,

everything would still be— something to be savored;

but everything isn't forever;

which is why we savor everything:

more than if it were.

We live in a fascist state

I don’t mean New York but the United States. If you follow the news and understand it, you know we are no longer in danger of sliding into fascism or living with a leader who exhibits fascist tendencies. We are living in a fascist state.

There is no “silver lining” to dementia. For the sufferer or the caregiver. Only love is a balm, and it’s clear you have that. Wishing you peace and the grace to keep going despite the pain.

I would not say "Bright Side" My mom passed 3 weeks ago today. Traveling through 4.5 years with her living with me and years of support out of state. It was an experience like nothing I have had or could imagine. What often helped me was not talking, and not having expectations. following her lead. ( She was considered easy by most standards lol) Still 24/7 care, incontinence, very little understanding as things progressed. My thoughts and emotions as I traveled through and now can be so varied. We try to make sense out of our experience right? The only "grateful" is that I am still alive and was somehow able to care for my mother who had a horrible disease. Get as much help and support as you can.