`It can't happen here' is fiction; it can happen here

Ken Burns commencement address may just give you some hope for future

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

It can't happen here.

If you are like me, if you've been paying attention to the politics and the opinions of your neighbors for the past decade, then you know what I'm talking about.

You are worried.

Some days maybe even a little scared.

And while you may be discouraged by the news and views you see all around you, I suspect deep down as an American, as a student of our history, as a patriot, you believe, ultimately, that it can't happen here.

Democracy will prevail.

The checks and the balances will hold.

Leaders will do the right thing.

Anything other than that is is unimaginable.

You have faith the parchment the Constitution is written upon is strong enough to defy destruction.

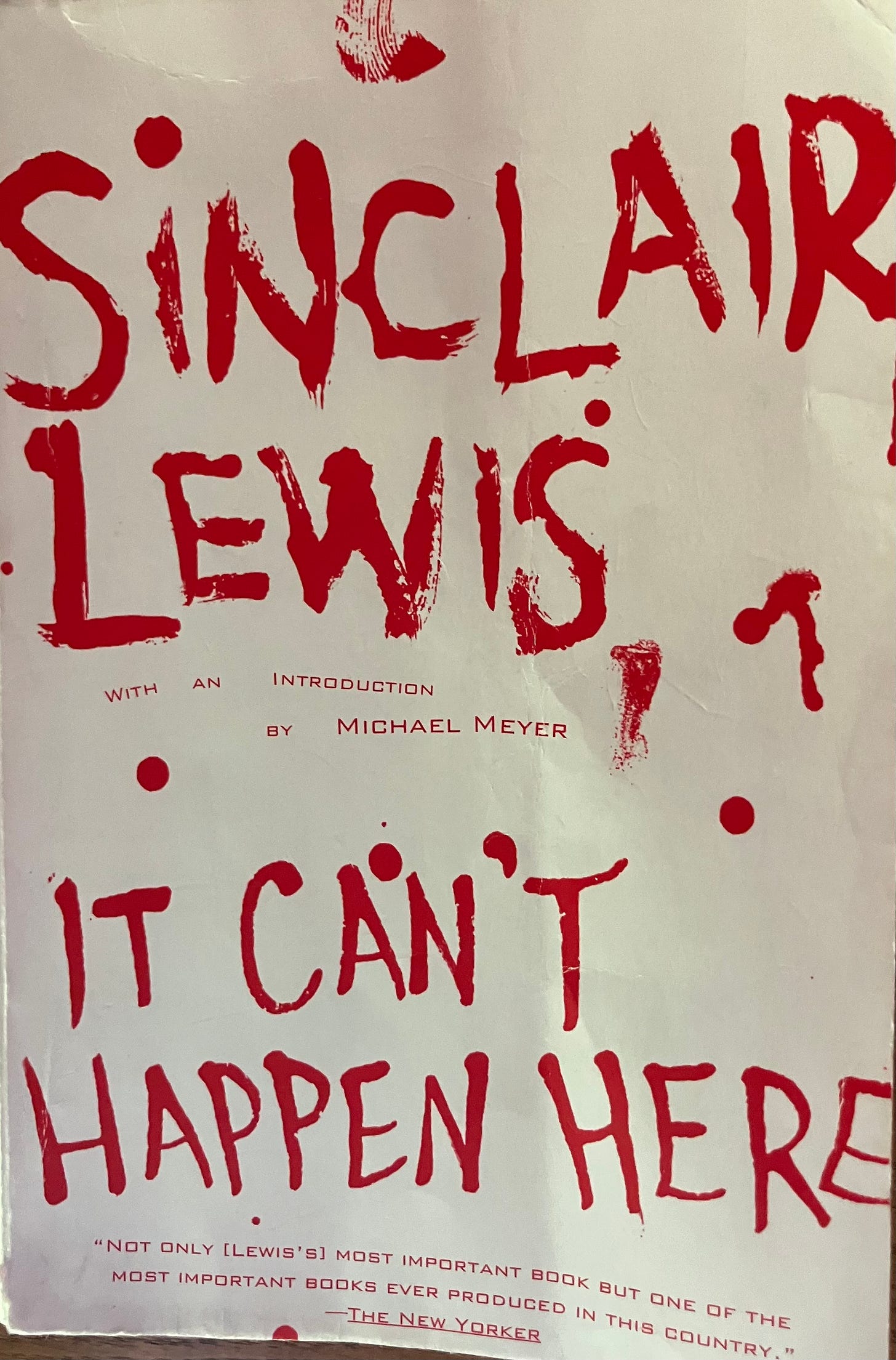

Five months ago, I received a package in the mail.

It was from Dave Whitman, a reader who shared my fears about a second Trump presidency. Inside was a Sinclair Lewis novel written in 1935.

I was not familiar with the book and don't remember reading any of Sinclair Lewis' work before.

Whitman told me he had read Lewis' novels in high school, but had not read It Can't Happen Here until recently.

He said it spoke to today's "situation."

He wrote he had been meaning to get me a copy for some time. I'm not sure what the impetus was to do it now, but perhaps he believed we were running out of time.

A month ago I started reading the fictional story of a populist presidential candidate capturing the imagination of the people in the midst of a world-wide economic depression, rising fascism in Europe and a general feeling of discouragement in the country. Lewis was writing first-hand about what he was seeing in the United States in 1935 and predicting the future.

Many of us may have forgotten there were other forces at work besides the Depression in 1935.

"He found a ready-made plot in the nervous undercurrent that accompanied the volatile politics of the period," wrote Michael Mayer in the book's introduction. "With the rise of Adolph Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Europe and the alarming popularity of a variety of demagogues, from both the left and right in the United States, there was widespread concern that the country could be taken over by a fascist dictatorship."

The book became a national best-seller as Lewis incorporates real political leaders like Franklin Roosevelt, Huey Long and the radio priest, Father Coughlin.

What I found so compelling was the similarities between the mood of the middle class country in 1935 and today and the popular appeal of a presidential candidate portraying himself as one of the people.

Lewis paints a picture of an angry electorate looking for a better way of life, distrustful of government and tired of struggling to survive.

The novel portrays presidential candidate Sen. Berzelius Windrip - you can call him Buzz - selling voters on a "Fifteen Points of Victory for the Forgotten Man" platform. I saw the similarities with "Make American Great Again."

Windrip courts the regular working-class American who feels forgotten and betrayed.

He promises a mass distribution of the wealth in the country where every man will be guaranteed a $5,000 income. That's $114,000 in today's dollars.

The story is told through the eyes of a liberal small-town Vermont newspaper editor, Doremus Jessup, and the regular people he associates with every day.

With the election approaching, Jessup explains the ramifications of Windrip's election to his wife and what it could mean to the country:

"They've realized this county has gone so flabby that any gang daring enough and unscrupulous enough and smart enough not to seem illegal, can grab hold of the entire government and have all the power and applause and salutes, all the money and places and willin' women they want."

That sounded familiar to me as well.

"But will Americans stand for it long?" the editor's wife asks.

"Dunno," Doremus Jessup answers. "I'm going to try help see they don't."

That's how I would have answered. That was the role of newspapers in 1935.

It was the role of newspapers when I was an editor not too long ago.

By the time I was halfway through the novel, I still felt It can't happen here was an accurate title. But then I was reminded of the 2016 presidential election when no one believed Donald Trump could become president.

For those of you book-readers out there, there is no way to tell this story without spoiling some of it. You've been warned.

Buzz Windrip is elected president and during his first week in office begins implementing his "Fifteen Points of Victory for the Forgotten Man" which includes actions to take the vote away from Negroes and force all women out of the workforce and back into the kitchen.

What seems impossible - even in fiction like this - now seems credible when the forces of evil know how to manipulate the people and which levers to pull to get what they want.

It's a reminder of the fragility of freedom and why our democracy is so often called an "experiment."

What Lewis exposes with his observations is the simplicity in which it can be done by just a few people with the terrifying results.

It was a warning in the days before World War II. It is also a warning for our time.

Consider this description of the future president Buzz Windrip and see if you are reminded of someone else.

The Senator was vulgar, almost illiterate, a public liar easily detected, and in his "ideas" almost idiotic, while his celebrated piety was that of a traveling salesman for church furniture, and his yet more celebrated humor the sly cynicism of a country store. Certainly there was nothing exhilarating in the actual words of his speeches, nor anything convincing in his philosophy. His political platforms were only wings of a windmill.

What I found even more haunting was the anger from the working class as they were given power over the professionals, the teachers and what would be called the elites.

As I perused social media after the Trump verdict on Thursday, that anger, that sense of grievance, that need for revenge reminded me of It Can't Happen Here and it was becoming more and more clear that it could happen here.

Part 2 Wednesday: The fight to save democracy

Burns gets it right

As a historian and documentary filmmaker, Ken Burns has always tried to have what he calls a "neutrality" in his work.

Last weekend, he announced during a commencement address at Brandeis University in Boston that he could not longer do that.

He spoke out about this moment in our history and the existential threat we all face.

We saw it play out this past week after Donald Trump was convicted and Republican politicians all over the country condemned the rule of law.

I urge you watch the entire 21 minutes of Burns' speech.

It might help you to get through the days ahead.

Sign of times?

From time to time, I lament the simpler, more neighborly days from a decade ago before Donald Trump.

Four years ago, a homeowner on Aviation Road put up a sign on their fence that boldly proclaimed that Trump was still their president.

Four years later, the sign is weathered, faded and becoming harder and harder to read as the brush and bushes around it obscure its message.

I'm hoping it is a sign for the future.

The tabloids

When I was working my summer job in Connecticut before my senior year of college, almost all the workers started their day with one of the New York City tabloids.

I preferred the New York Daily News because I liked their sports columnists Dick Young and their Yankee beat writer, Bill Madden. These were the George Steinbrenner years where the Yankees were always on the back page as part of some big controversy.

Tabloids do not have home delivery. They are hawked on street corners and subway platforms and depend on impulse buys to make their money.

Their coverage of the mob, crime stories and sports were screamed out in enormous, often creative, headlines that made you chuckle and more often than not forced you to buy the paper.

I don't remember either of the tabloids being very political during the 1970s. Every politician was fair game.

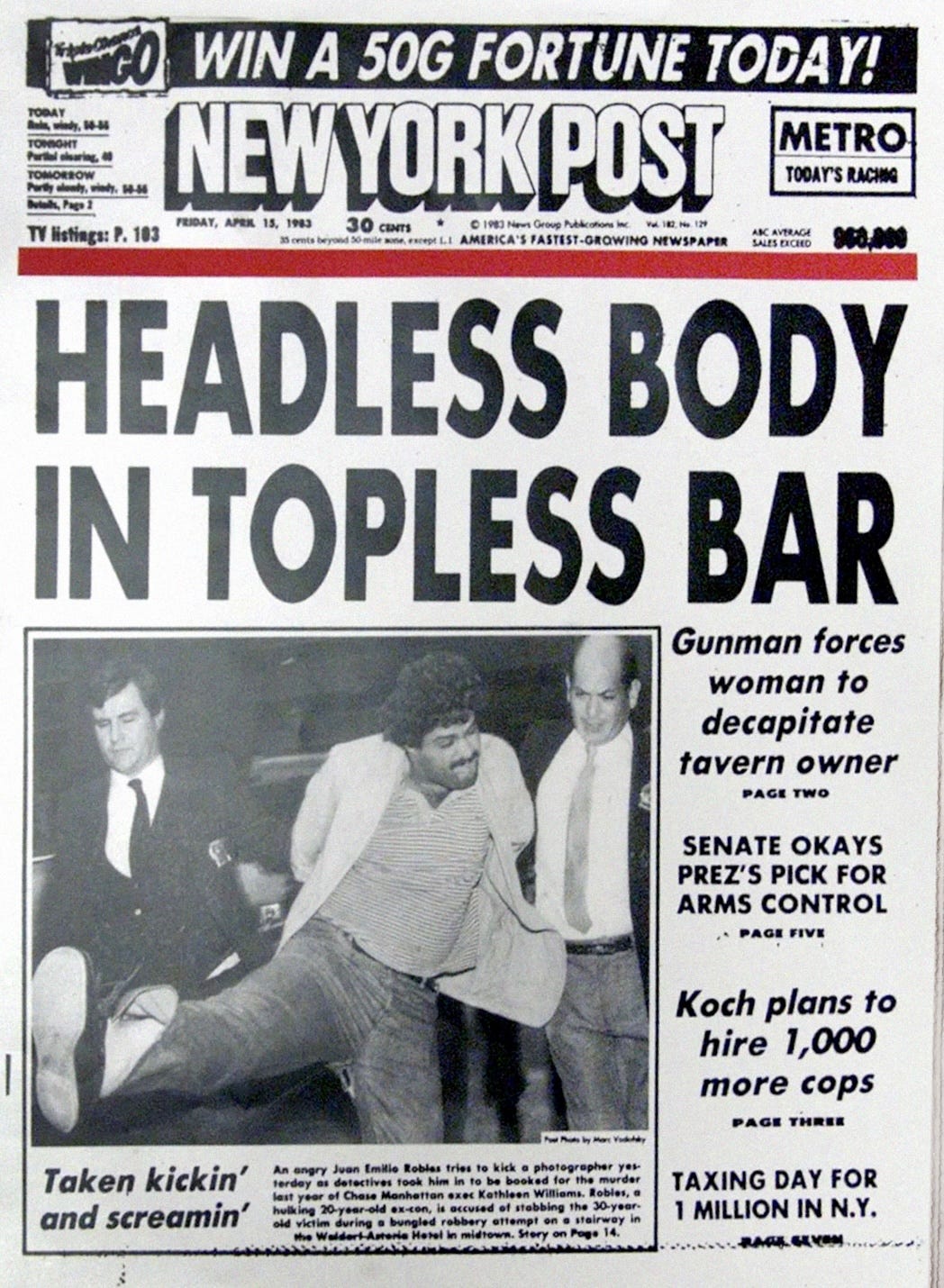

The New York Post published one of the most famous headlines of all time:

Headless body

in topless bar

It makes me chuckle to this day.

Neither of the New York tabloids have been a bastion of journalism ethics over the years, but they used to stay clear of politics.

But soon after Rupert Murdoch's NewsCorp purchased the New York Post - its sister company owns Fox News - it began showing its political opinions in those enormous headlines.

So after the the Trump verdict was announced last week, we saw headlines like "Guilty" and "Trump convicted" in big, bold headlines appropriate for the weight of the news.

But the New York Post headline read "Injustice" and a subhead "NYC jury makes Donald Trump first felon president after political hit job."

That was an opinion in 200-point type.

It was inappropriate.

It's why when people quote from stories in the New York Post - Hunter Biden laptop stories for instance - it is hard to take them serious.

This further cements the Post's reputation as a newspaper not to be taken seriously.

Ken Tingley spent more than four decades working in small community newspapers in upstate New York. Since retirement in 2020 he has written three books and is currently adapting his second book "The Last American Newspaper" into a play. He currently lives in Queensbury, N.Y.

"When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in a flag, carrying a cross". My research of this quote just last week led me to this very book written by Sinclair Lewis. The phrase so reminds me of Trump hugging the flag and hawking bibles.

“There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn't true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true.” - Soren Kierkegaard