For Alzheimer's caregivers, there's only a difficult now

Tolls by Mail thinks I was in Buffalo

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

Bella sleeps so much these days.

Perhaps she is trying to heal.

By late afternoon, she is drooping, and by 6, sprawling on the bed, where she stays, more or less, for 13 hours.

Yes, she’s usually up at least once during the night and often several times, wandering the house.

I go to bed when she does, get up during the night when she does and wake up at about 3 to tiptoe downstairs, put on the coffee, do a couple of word games on the New York Times site and climb back up to the office — next to the bedroom — to write, as I’m doing now.

Bella seems to sense me there and rolls out of bed and comes squinting into the hallway. I give her a hug.

“It’s 4 in the morning. Do you want to go back to bed?” I say.

“Yes,” she says, and I tuck her in.

She gets up around 7, and we brush our teeth and go downstairs and have coffee and toast in the library. I give Bella her morning pills. If we don’t have a reason to go out — today, which is Tuesday, we’re getting flu shots at 9 — she will doze on and off through the morning, sometimes in a chair and sometimes back in bed.

Occasionally, we’ll go out for a walk in the morning, then get a hot chocolate somewhere — recently, at the new Uncommon Grounds in Queensbury.

Bella wakes up for the afternoon. Sometimes, she’s agitated, wandering the house, opening the front door and taking in the cold and snow, saying in a pleading voice she wants to go home.

I’ve been told this wish is common among Alzheimer’s patients. What “home” means isn’t clear. It could be a longing to return to the warmth and safety of a childhood home, although Bella’s childhood home wasn’t warm and safe.

I think she longs to go back to a time when she could think for herself and speak her mind and face the world unafraid. She wants to return to the strong self she created, which has been taken away.

Early on in the disease, I drove her around Glens Falls to look for the home she yearned for, and after an hour or so, she was willing to give up.

A couple of years ago, we drove up to her old house in Lake Placid, parked in the driveway and knocked on the door. No one answered.

“I think there are people in the other side. I can hear them,” I said.

We walked to the back, where two big dogs were chained. They were thin and hysterically happy when we petted them. Bella insisted on confronting the residents about the dogs. She knocked on the door, and a man and a woman came out and told us it was none of our business.

Back in the car, Bella asked me to report them to the police for neglect, and I made the call, although I doubt anything was done.

Now, she worries about our dog, Ringo, all the time.

“Where’s the baby?” she says.

“Right here,” I say, waving a hand at him.

We take Ringo for walks, even though Bella doesn’t like the cold or the snow or, in the evening, the shadows across the sidewalk.

Her steps are slow and unsure. Monday, she slipped on the snowy road in Crandall Park and fell to one knee. I tried to lift her up, but she wasn’t helping. She couldn’t figure out how to stand.

“Stand up,” I said, pulling, and we finally managed it.

I don’t want to stop our walks. So much has been stopped — almost everything except eating and sleeping and showering and using the toilet, and even those aren’t second nature for Bella anymore.

I savor the few seconds of exhilaration I feel now and then on our walks, with the cold wind in my face.

Sometimes, we watch a show or a movie in the afternoon, but it’s difficult to hold Bella’s attention for more than a few minutes. She might walk downstairs in the middle of a movie and sit at the dining room table with her chin in her hand, eyes closed, or in a cushioned chair in the library with her head tipped back.

If she’s really asleep, I call my sister or brother, my mom or dad or one of my kids for the conversation I thirst for. I try harder to listen now that my own main listener usually can’t understand me.

Our Alzheimer’s journey started in February 2017 with Bella’s diagnosis. Early on, in the first year or two, I met a man whose wife was much farther gone. He seemed so tired — emptied of liveliness — and it scared me.

Caregivers can’t see the road ahead. All we can do is walk it, usually in slow motion, and all we can hope for is that we will endure.

Modern life

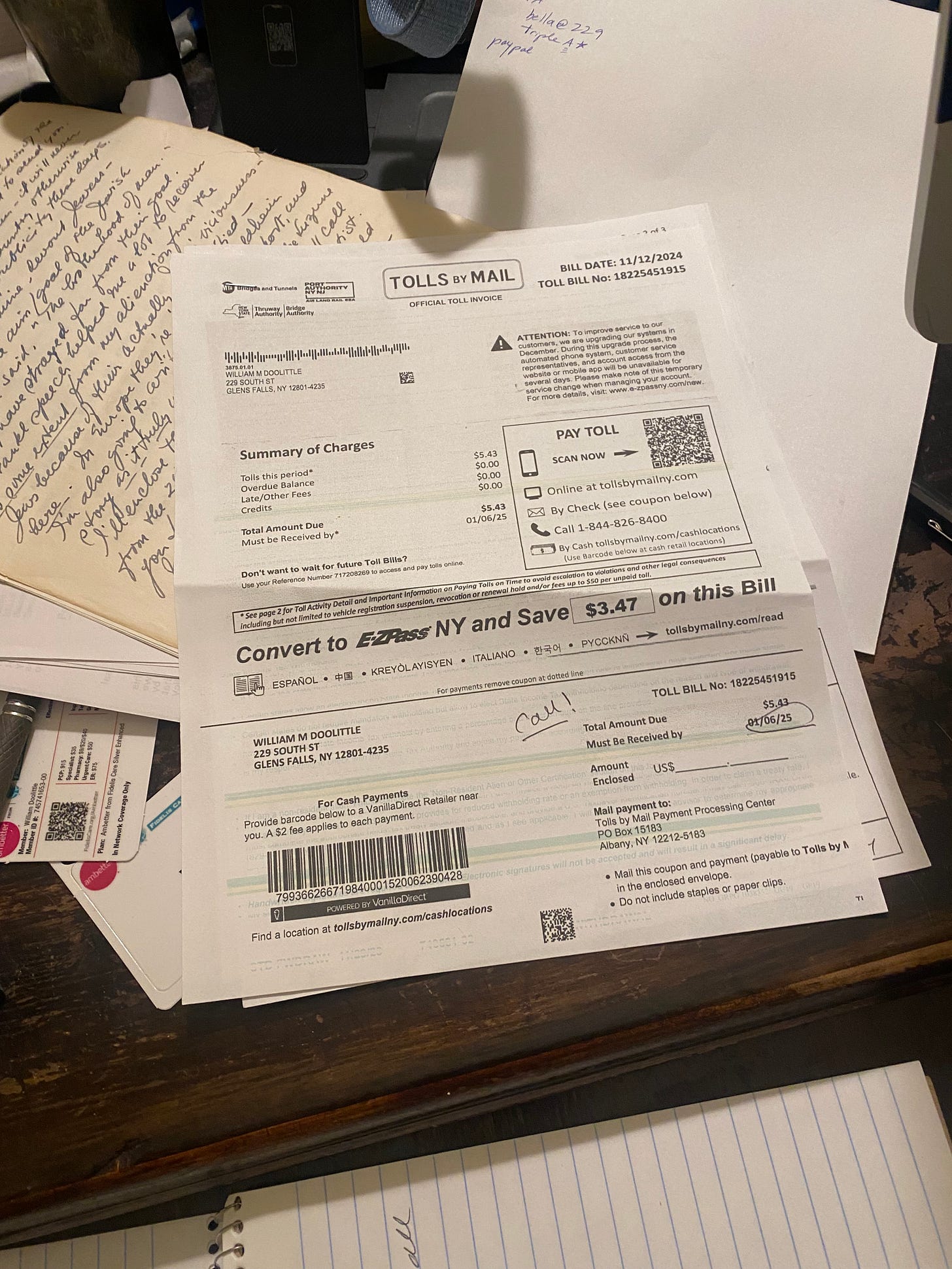

A few weeks ago, I received an “official toll invoice” from Tolls by Mail, the organization that collects tolls for the NY Thruway Authority and Bridge Authority, Port Authority NY and NJ and MTA Bridges and Tunnels, when drivers use toll roads and bridges without a functioning E-Z Pass transponder.

The bill was for $5.43, comprising $3.43 for the toll at Exit 50 on the NY State Thruway at 6:56 p.m. on Sept. 28 (a Saturday) and $2 for the “toll admin. surcharge.”

A couple of things about this bill: First, Exit 50 is about five hours west of here, outside Buffalo. It’s the exit for Niagara Falls and I-290, and I’ve only been to that area once in my life, 10 or 12 years ago.

Second, the license plate listed on the bill is not the plate on our car, and we own only one car.

The Tolls by Mail bill came with a photo, meant to be one taken of my plate as my car passed under the E-Z Pass gantry at Exit 50. The photo is black.

I called the Tolls by Mail customer service number and reached within a few minutes a human being who could speak and understand English. I explained to her a mistake had been made.

She asked for the number on my transponder and, checking it, found it was working. She also confirmed it was the right transponder for our car, after I looked out the window and read off our license plate.

Our plate and the plate listed on the bill share only one letter — B — and one number — 0 — out of three letters and four numbers on each. So it seems unlikely the plates were confused, although, with that photo, who knows?

I explained to the woman my wife and I are in bed or nearly so by 6:56 p.m., and we were nowhere near Exit 50 that day.

She said to dispute the bill, I’d have to request a NY vehicle registration abstract under my name from the Department of Motor Vehicles, and send it in, along with a copy of the bill.

“But you guys made the mistake, not me. I realize it’s not you personally, but you see what I mean? Why should I have to prove I’m not the person you mistakenly think I am?” I said.

She understood. But she has to follow the rules, however unfair, to keep her job, just as I have to if I want to keep driving.

So I went about obtaining a copy of my NY vehicle registration abstract, which I discovered cost $10.

If I had paid the bill I don’t owe, I’d be out $4.57 less than it is costing me to prove the bill was mistaken.

But I ordered the abstract, because I feared that paying the bill could be taken as confirmation of the mistaken identification, and that might lead me down a Kafkaesque path.

Before long, two men would be at my door, explaining I was being charged with crimes they would not reveal.

I got the abstract, which shows I do not have a car with the license plate listed on the bill, and mailed it in, along with the bill.

Now I wait. I don’t know how they intend to confirm their mistake, if they do. Perhaps they’ll keep me guessing.

Bad Plates

I began noticing a year or so ago license plates that appeared to have had their paint scraped off or been intentionally crumpled. I’ve also seen cars with plates that have heavy plastic covers that make the plate numbers hard to read. I assume these are all attempts to dodge the E-Z Pass cameras and get out of paying tolls. I’ve taken a couple of photos of altered plates, but I’m hesitant to publish any without knowing for sure how they got that way. But I’ve seen enough of them around to be certain this is no natural process or result of an accident.

So the difficult behavior goes both ways. Yes, it’s absurd I have to pay $10 to prove I’m not who the EZ-Pass camera mistakenly thinks I am. But it’s also a problem that thousands of New Yorkers (there have been stories about this) are intentionally altering their license plates to get out of paying their fair share of tolls.

Thank you Will, I do hope you eventually publish your "alzheimer's experiences" for the world to see. My step-mother Jean died of this disease, and you have chronicled much of her journey. The driving around at 2am looking for "home", which in this case was Hudson Falls, outbursts for no reason, sleeping for long hours, living much inside herself. This fell mainly on one brother and sister...they are saints as you are. You're in my prayers daily. God Bless you Will. May the Holidays bring you some peace and warmth... Mary Ellen

Caregiving is hard work; emotionally, physically, spiritually. I've learned that the unwanted change in lifestyle is the most difficult part. You allude to that when you mention missing your partner who could share so much with you. I so often hear that we must learn to live one day at a time, not regretting the past, nor fearing the future. Caregiving forces us to do just that. Words are not adequate to express how much I admire your courage and willingness to share your experience.