The Front Page

Afternoon Update

Tuesday, October 19, 2021

By Ken Tingley

After listening to author and climate activist Daniel Sherrell speak three weeks ago at Albany Book Festival, I wrote in this newsletter “We are a total failure.”

I was speaking for my generation.

I was speaking to my son’s generation.

I was speaking to our total failure to address the cataclysmic advance of climate change.

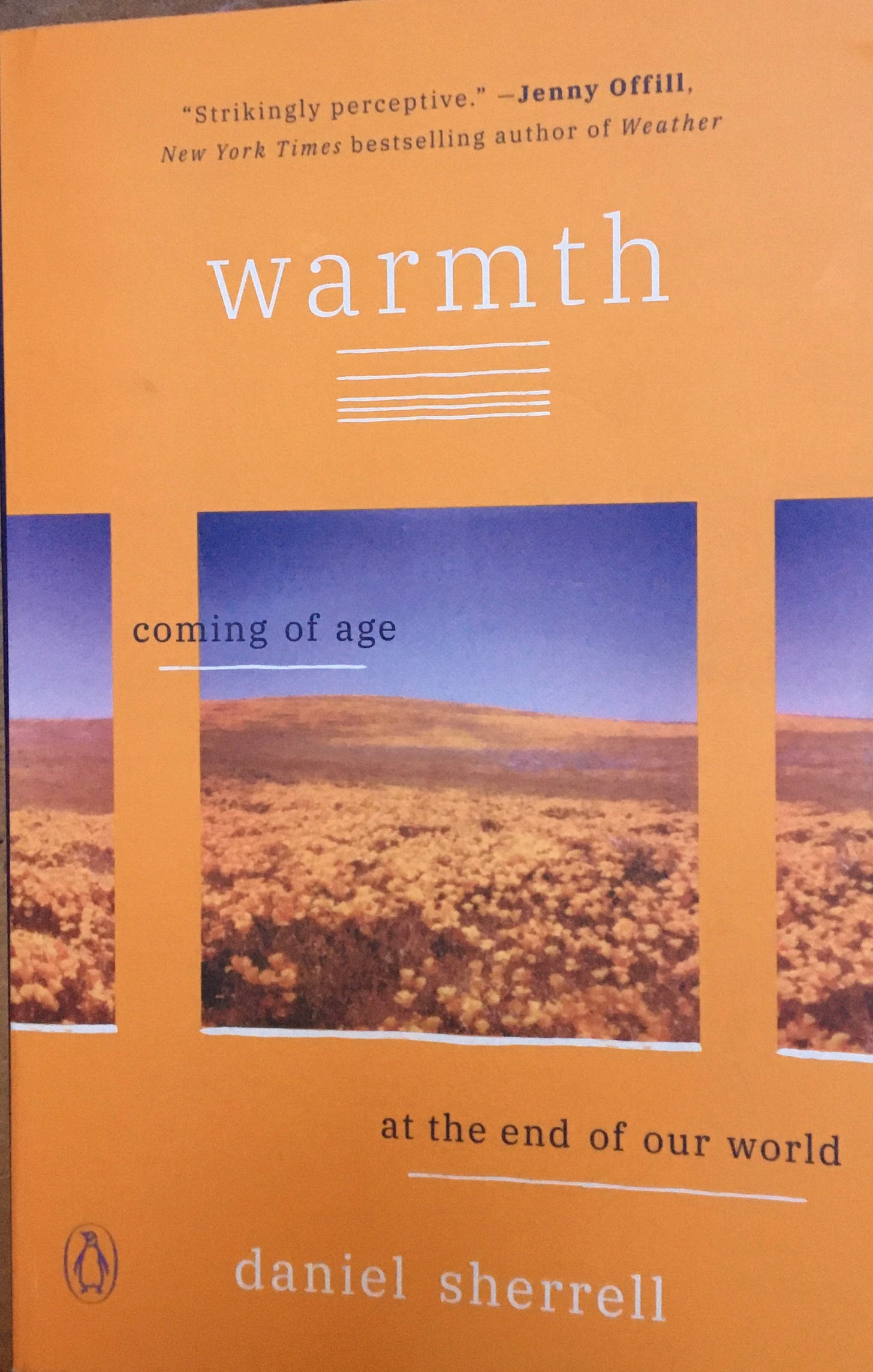

Since then, I have finished reading Sherrell’s book “Warmth: Coming of age at the end of our world.”

Sherrell is a 31-year-old activist and organizer who is credited with helping to pass landmark legislation in New York - the “Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.”

While speaking, Sherrell made it clear he didn’t want to write another book about climate change. He actually never uses the words “climate change” in his book. Instead, he repeatedly refers to it as “The Problem.”

After finding a career as an activist, he addresses the ongoing despair he feels about a future that may be bleak for him and his generation.

It is a problem my generation never had.

We always knew there would be a tomorrow, so we worked diligently to make sure it would be a better one. But apparently, not hard enough.

The question Sherrell addresses is: What’s the point of getting up and going to work in the morning if there is no future?

The debate is topical, too. Democrats are pushing for landmark legislation to address climate change by forcing utility companies to produce cleaner energy. Republicans are opposed to it. Sen. Joe Manchin, a Democrat from from coal rich West Virginia, may very well have the future of the planet in his hands as he refuses to go along with planet-saving measures that might cost his state jobs.

Can’t someone get Sherrell and Manchin in a room for 30 minutes?

But again, this is not the point of Sherrell’s book. He is not trying to change anyone’s mind about climate change, but to share the dread he and his generation feels about the future that may be written in stone.

He explains the book is a letter to an unborn child he may or may not ever have as he tries to explain why he is cautious about bringing a child into a doomed world.

As I read “Warmth,” I considered sending my son a copy of the book. I thought he might find it comforting that there are others his age who have the same worries about the future and the world he will inhabit.

Each time, I paused.

I wasn’t sure if reading Sherrell’s words wold make his outlook brighter or darker.

Sherrell talks about the grief he often felt after getting an alert on his phone about the latest superstorm.

“This was a weight I kept private mostly, unsure of whether or how to share it,” Sherrell writes. “Even with my closest friends, discussions of the Problem tended to stumble into the arid gully of knowing commiseration. `We’re so fucked’ is what we let ourselves say, on the rare occasion the conversation wasn’t quickly diverted into lighter terrain.”

But that barely touches on the despair for the author.

He described reading an article on the subway one evening that he had been meaning to read for months.

“The thesis was basically that there were no longer any paths to avoiding catastrophe without the large-scale deployment of atmosphere carbine removal, and that large-scale atmospheric carbon removal was for all intents and purposes impossible,” he wrote. “Putting away my phone, all I could muster was a dull outrage that it’d taken me months to find out that the end of the world had been convincingly proclaimed on page seventy-two of the November 2017 New Yorker.”

I sometimes wondered if the only way to drive home the urgency was to run doom and gloom scenarios across the the front page of the newspaper every morning. But I didn’t do that.

For a time when I was editor of The Post-Star, I made it a point to read the latest United Nations reports about climate change. Each one was more pessimistic than the next. I wrote passionately about the need to address the issue for future generations, but there was never the urgency that I was personally at risk because I would not live to see the worst of it. But I have a son who may.

Sherrell remembers a colleague pointing out it was really bad luck the “Problem” was causing temperatures to rise instead of fall. She Imagined Chicago, Moscow and Beijing snowed in for months while poor equatorial communities began donning sweaters.

“We probably would’ve tackled this thing forty years ago,” his friend said.

“Joking, but also not at all,” Sherrell wrote.

The point was that if hurt the gross national product of rich nations instead of those that our poor, the problem becomes more urgent.

Sherrell points out there are already hedge fund investing in products related to surviving in a catastrophic future where the rich will buy large tracks of land where it still rains regularly.

The end won’t happen all at once, it will happen gradually over decades with the quality of life eroding slowly with more people dying in storms and floods. Eventually crop failures and food shortages will affect our children’s quality of life.

I think we all struggle with that concept.

At one point, Sherrell writes this in his letter to his unborn child:

“I’m sharing this with you because I want to convey what it was like to feel that we were losing. To look up at the glass face of an arbitrary skyscraper and know that the storms were getting worse and that thousands more were going to die. To know that many people were working very hard to prevent this - legislators, engineers, artists, activists - and that these efforts were, at least so far, nowhere near adequate. And to keep trying anyway, to tread the luminal ground between denial and resignations, not always buoyed by hope so much as the terror of what giving up would force us to admit to ourselves.

So that’s where I am.

What does “giving up” look like.

Last week, I noticed there was going to be a meeting this Thursday about the future of the Hudson Falls trash plant, one of the worst polluters in the state.

What to do about it?

What is its future?

In the grand scheme of climate change, it’s a rain drop in the ocean. But we all should do something. If not for us, then for our children.

I will be there at the Sandy Hill Arts Center in Hudson Falls. It begins at 6:30 p.m.

Film Festival winners

I saw close to a dozen movies over the weekend at the Adirondack Film Festival. It was a great chance to see films of all types.

As I said previously, “The Russian Five” documentary with all those connections to Glens Falls hockey was my favorite movie.

Here are the award winners:

Best Narrative Feature - Lie Hard

Best Documentary Feature - Missing in Brooks County

Best Home Grown Short/Best of Fest: Odyssey

Best Narrative Short - Duality Derby

Best Music Video - Candy Store

Best Experimental Short: How to end a Conversation

Best Documentary Short - One All the Way

Tweet of the Day