We must accept what is not enough

I don't know what to do about City Park

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

Bella didn’t transform into someone else when, in February of 2017, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, and our lives didn’t change much.

We both kept working. We didn’t tell the kids right away. We continued to laugh at and with each other.

Bella questioned whether she really had the disease. I shrugged it off.

“Nothing’s different,” I told people. “Maybe it will be, but it’s not now.”

But my mom started crying when I told her.

“I feel so sorry for you,” she said.

“It’s OK. I’m OK,” I said.

I didn’t know much about Alzheimer’s. I’d seen my grandmother babbling and circling her living room with her walker. But I couldn’t imagine Bella that way.

As the months passed, I noticed she seemed jollier. Her edges were less sharp, which wasn’t bad.

But that was the beginning of the attack on her personality, which has continued over the last eight and a half years, clouding her memories and her abilities until not much is left of the vital, happy, stubborn, passionate, insightful person she was.

Just the love is left. And the stubbornness.

But even those qualities get overwhelmed by fear and confusion, as she loses touch with her body and struggles to hold a fork or step off a curb or use the bathroom.

Her moods swing from one minute to the next, and I hesitate to go out now to walk through downtown with Ringo and buy a pastry for each of us and a cup of coffee, because when we come back, she feels we’re at the wrong place and won’t get out of the car. Or she does get out and leaves, walking around the corner on the sidewalk and up and down the block for an hour or more.

In the first few years following her diagnosis, after she was forced out of her job and I quit mine to stay home with her, I was flummoxed by the unpredictable, inexorable progress of the disease.

I was flailing, underestimating the extent of her symptoms and failing to prevent dangerous situations.

Once I came out of the grocery store to see Bella pulling out of the parking lot, because I’d left her in the car with the keys. She should not have been driving.

When she went on walks, I tracked her by her phone in her purse, but more than once she left without the purse or put it down somewhere and I lost her and drove around trying to find her and had to call the police.

She’s not so bold anymore and easier to keep safe. At night, I lock the doors with little slide bolts placed up high.

I try to stay healthy by exercising and eating well, reading books, talking with people on the phone and sometimes scheduling our respite caregiver to come so I can meet a friend at a coffee shop.

Every time I’m stretching out on the rug while she’s slumped in her chair, or eating yogurt and blueberries while she stares at the wall, or chatting on the phone while she wanders between rooms and hovers uncertainly in the hallway, I feel a tinge of shame.

Maybe she wants to talk to me. Maybe she’d be happier if I sat quietly in the same room with her. I should do better with her meals. I should keep trying and not give up on her.

I realized years ago I was going to always feel I was failing at caregiving. I resolved to accept that and do my best, but that didn’t change anything. I still feel the job could be done a lot better.

For awhile, early on, I had a recurring daydream she would suddenly be all better. Probably this arose from seeing her apparently healthy every day even though I knew she was terminally ill.

But the evidence of her sickness is overwhelming now and I don’t have that daydream anymore. The blankness in her eyes, her hesitancy in doorways, her inability to put together more than a handful of words.

Now I start each day with the hope the day passes quickly. I track the hours.

Bella has moments of pure love and affection. Her face gets flushed, and she stares at me or one of our kids with eyes wide and says, “I’m so glad you’re here. I love you. I love you. You’re nice. You’re a nice person. I love you.”

Her good moments have just a hint of who she used to be. That’s all we get these days, those of us who love her. It’s not enough but it has to be.

Poem

Here is a poem by Hudson Falls poet Richard Carella:

Weight of Nothing

Nothing weighs

nothing...

and yet:

must

be borne.

Hokusai

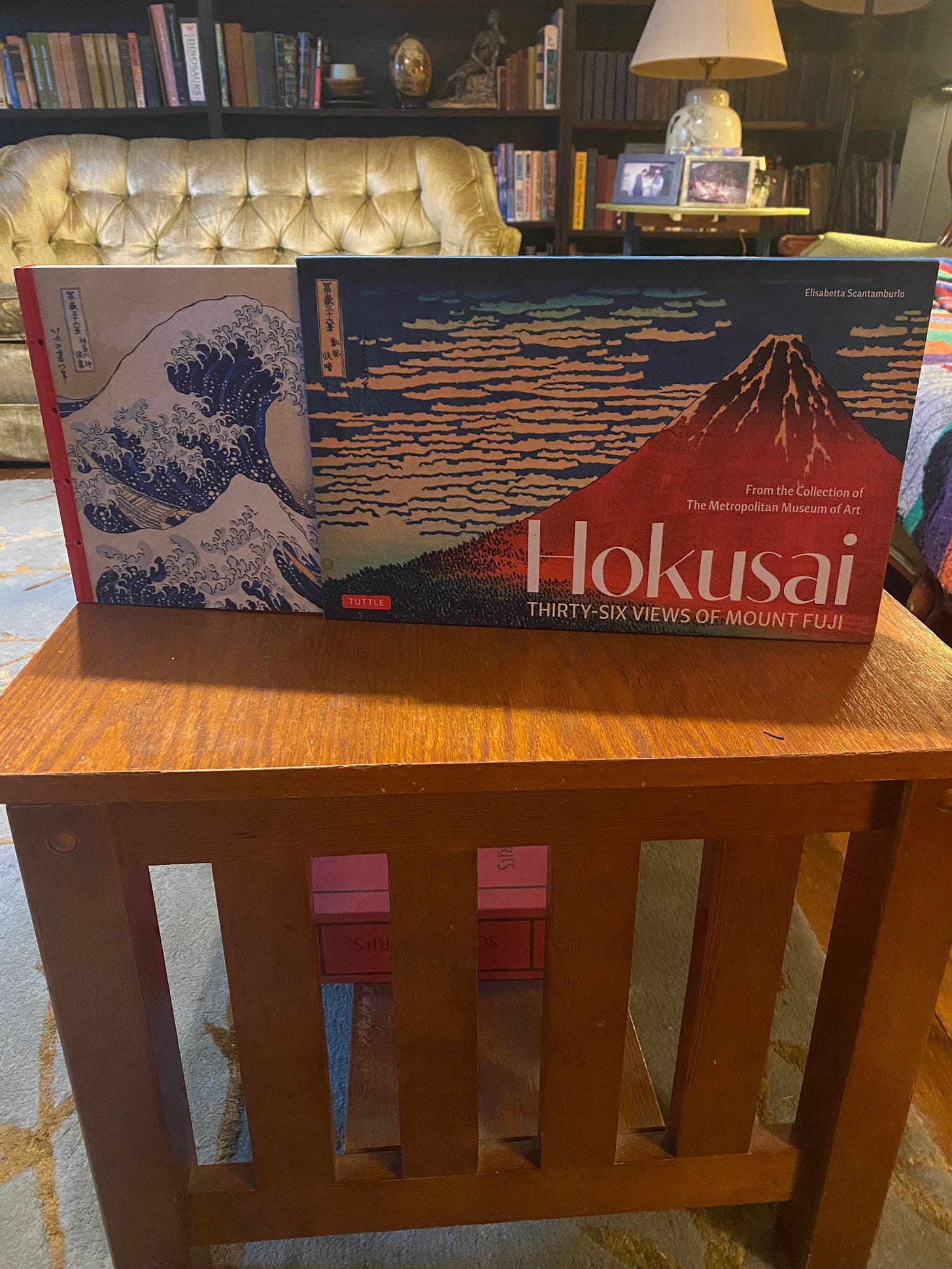

My daughter Ginny got me a Hokusai book for my birthday, a collection of reprints of his series of prints, “36 Views of Mount Fuji,” along with an extra 10 views of Fuji he and his publisher decided to put out after the series became a hit in the early 1830s in Japan. Hokusai was in his early 70s at the time and, according to him, just hitting his stride as an artist. He was no Van Gogh, lacking appreciation in his lifetime. He was more like Shakespeare, appreciated, popular, making a good living doing what he loved but not hailed, as he would be later, as one of the greatest artists of his time or any time. A couple of his “views” — the one on the slipcase, known as “Red Fuji” and the one on the cover, known as “The Great Wave” — are so well-known most people are familiar with them. But to really appreciate how elegant Hokusai’s work was, how creative and playful he was, how he seamlessly incorporated eastern and western techniques in pictures of perfect balance whose effect is both dramatic and understated, you have to look at more than the most famous prints.

City Park

If this were to be your only column incorporated into medical school and nursing school curriculums, it would become a teaching tool of immense value in enlightening future health care providers about the many dimensions of dementia…and the impact on caregivers. Everything you write about will never be found in a textbook, but hopefully someday you will publish a book about your journey with Bella.

In the meantime, you are providing insightful guidance to your Front Page readers who are in the different stages of caring for a parent, spouse or other loved one in the here-and-now…and providing solace to those who have done all that they could, for as long as they could, with or without the support of homecare resources. Nothing ever feels like it’s “enough” when caring for anyone with a terminal illness, but Alzheimer’s robs us of the capacity to use words to understand and comfort one another in the later stages.

Praying for your strength and endurance to continue your holy work…🙏

I know you are not looking for this but in the world of service, you are a shining example of what it looks like.