The legend of Norman Rockwell: We are never too old to make a difference in the world

By Ken Tingley

For me, artist Norman Rockwell was a story-teller.

Best known for the “Four Freedoms” paintings used to sell war bonds during World War II, Rockwell was legendary for capturing the lives of everyday Americans in his illustrations.

When I visited the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass. recently, I rediscovered Rockwell.

Or more precisely, a different side of Rockwell.

His long relationship creating covers for the Saturday Evening Post made him famous, but in an interview later in life, Rockwell lamented how the magazine had once asked him to remove a black person from a group illustration because Its policy was to only show blacks in service-industry jobs.

That obviously stuck with him.

Found among his papers was a 3 a.m. note from May 1963 when he was 69. He was apparently wrestling with ending his 45-year relationship with the Saturday Evening Post.

“All of this debasement, depression, unsatisfaction. Isn’t this the answer - if necessary, die doing something worthwhile,” Rockwell wrote. “A worthy end .. not humiliations, fear and groveling. Have I got the sustaining courage to cut it through?”

Rockwell seemed to be making an argument with himself about how to live the last chapter of his life.

Four months later, he told the Saturday evening Post he had “come to the conviction that the work I now want to do no longer fits into the Post scheme.”

On Jan. 14, 1964 Look Magazine published Rockwell’s illustration “The Problem We All Live With,” depicting four U.S. marshalls escorting 6-year-old Ruby Bridges into her New Orleans elementary school. There is a smashed tomato against the wall and the word “Nigger” scrawled.

For the first time in his long career, Rockwell received hate mail, sacks of it.

“Anybody who advocates, aids or abets the victims crime of racial integration is nothing short of a traitor to the white race, and a traitor to the illustrious white founders of this country,” wrote G.L. LeBon of New Orleans. “THE WAR HAS JUST BEGUN!”

But Rockwell changed attitudes, too.

“Allow me to say that I have never been so deeply moved as any picture as your painting in Look Magazine (14 January ‘64),” Chattanooga, Tenn. resident Chester Martin wrote. “Thank you for showing this white Southerner how ridiculous he looks. The truth is pretty hard to take until we get it from Norman Rockwell.”

Another person wrote, “YOU have just said in one painting what people cannot say in a lifetime.”

Then, Rockwell went deeper.

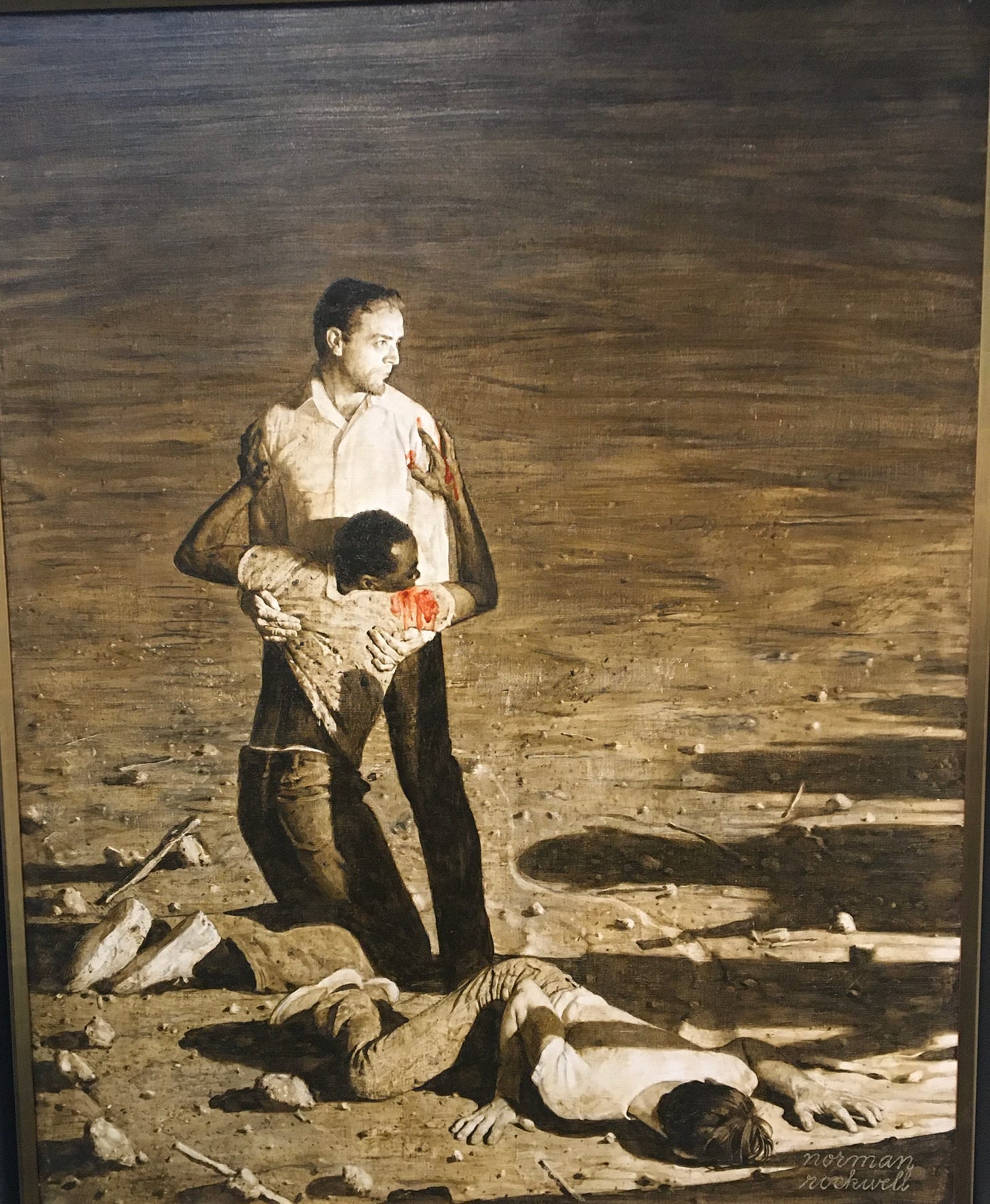

Found among his papers were newspaper clippings from the June 21, 1964 murders of civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Schwerner and Chaney, both from New York, were in Mississippi to assist with training summer volunteers in the civil rights movement. Schwerner had been targeted by the Ku Klux Klan for his organization of a black boycott of white-owned businesses and for his attempts to register blacks to vote in Meridian.

In March 1965, Rockwell began painting “Murder in Mississippi,” depicting the three civil rights workers in their dying moments at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. One is dead on the ground, one is dying and one prepares grimly for his own demise. It was published in Look Magazine on June 29, 1965.

The painting is powerful.

And important.

Once again, there was hate mail.

One man from New Orleans wrote, “just some more vicious lying propaganda being used for the crime of racial integration by such black journals as 'Look,' 'Life,' etc.”

When he left the safety of the Saturday Evening Post he was an old man.

But it allowed him to break new ground. As it turns out, Rockwell’s third act may have been his most important work.

He died on November 8, 1978 at the age of 84.

People still make pilgrimages to his grave to leave paint brushes and cans of paint.

Passing of Lloyd Mott

I first met Lloyd Mott when he was the athletic director at Queensbury High. But his best work might have been working at the New York State Public High School Athletic Association where he worked behind the scenes to make high schools sports better for the athletes.

He was also a big supporter of the New York State Basketball Tournament in Glens Falls.

He was one of those quiet, behind-the-scenes guys who always made a difference.

He passed away on May 3 at the age of 80.

Books for sale

It has been a great thrill to see this newsletter more than double its reach over the past year. I continue to receive an enormous amount of positive feedback as Will Doolittle and me try to fill a gap in local news coverage with our commentary.

For those of you who enjoyed by columns while at The Post-Star, I hope you get a chance to check out my collection of 83 columns in “The Last American Editor.”

I’ve also written a memoir celebrating the great work and journalists who worked at The Post-Star over the past two decades called “The Last American Newspaper.”

Both books can be found at Ace Hardware, Warren County Historical Society, Queensbury; Chapman Museum, Glens Falls; McKernon Gallery, Hudson Falls; Battenkill Books, Cambridge; Northshire Books, Saratoga Springs; and Corner Stone Bookshop in Plattsburgh.

And share the this newsletter with all your friends.

Ken, amazing depth re this subject. Thank you for your continued contribution on so many fronts. Very much applaud all you are doing for so many!!

That's a powerful piece on Norman Rockwell. Thank you for writing it.