Reading relieves anxiety and fuels it

An escape or a worrying reminder? Books, news stories can be both

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

I read too much on my phone, absorbing anxiety about politics through my eyes.

At the same time, I’m trying to make an easy, happy retired life with Bella, which is impossible, because she has Alzheimer’s disease. This effort leads to frustration and failures, guilt and shame and fretfulness and feelings of futility.

I turn to reading news stories on my phone and, especially, books to escape myself. Now, I’m reading “Vanity Fair” by William Makepeace Thackeray, a witty, satirical novel of early 19th century manners and history, published in 1848 and set in England during the last of the Napoleonic wars (1815) and continuing afterward. It serves the purpose of transporting me to another time and place, presenting a cast of buffoons and rogues and hypocrites and, in harmony with the subtitle — “A Story Without a Hero” — a smart, ambitious, heartless anti-hero, Becky Sharp.

“The Devils of Loudun,” by Aldous Huxley, published in 1952, also took me back in history recently, all the way back to 1630s Loudun, France, where, during a case of demonic possession at a convent of Ursuline nuns, a local Catholic priest, Urbain Grandier, is accused of being in league with the devil and having seduced the nuns in their dreams. In 1634, he is burnt at the stake.

The claims of satanic possession, followed by months of vigorous exorcisms and, finally, the execution of Grandier, are real historical events, described in contemporaneous documents. But Huxley fills out the record generously, using his novelist’s insight into human foibles to delve into the motivations of the townspeople, their envy and resentment of Grandier or, in the case of the convent’s mother superior, her frustrated desire.

That the whole extravagant episode was a sham was understood by at least some of its participants and by even more people soon afterward. In Huxley’s telling, Grandier’s downfall was caused by his proclivity for seducing other men’s wives and daughters, which made him powerful enemies who conspired to ruin him.

Along the way of telling this wild and disturbing story, Huxley treats the reader to disquisitions on the history of demonic possession and the legal and religious rules regarding its treatment, all of which were broken in the Grandier case.

In “The New Meaning of Treason,” published in 1964, Rebecca West explores the more earth-bound but equally misbegotten fever of fascism, which achieved modest popularity in England before World War II under its leader in that country, Oswald Mosley.

West focuses on William Joyce, who, like others in the movement, liked the club’s trappings and its propensity for violence in the form of street brawls.

It’s hard not to see parallels with Trump’s movement, with its emphasis on destruction of the existing system and playing dress-up with hats and flags and T-shirts meant to be offensive.

“It (fascism) had sprung up because people who, living in an established order, had no terror of disorder had read too much in the newspapers about Mussolini and Hitler and thought it would be exciting to create disorder on the same lines,” West writes.

And, a few pages later:

“Mosley had taken a black old building in King’s Road, Chelsea, formerly a teachers’ training college, where he housed his private army of the whole-time members of the British Union of Fascists, and there life was a boy’s dream. Uniforms were worn that were not really uniforms, that at once claimed and flouted authority, as adolescence does … corridors were patrolled by sentries beetling their brows at nothing, executive officers sat at desks laden with papers alluding to mischief as yet too unimportant to justify authority in taking steps to check it; dead-end kids that could call what was dead alive and the end the beginning, innocently and villainously filled rubber truncheons with lead. There is nothing like infantilism for keeping the eyes bright and the skin smooth.”

Unlike most of the English fascists, who abandoned their play-acting when England declared war, Joyce stuck with the movement and skipped off to Germany, where he was used by the Nazis as a radio propagandist. Frequently referred to as “Lord Haw Haw,” Joyce touted the strength of the Nazi forces on air and encouraged English soldiers and civilians to give up. His broadcasts likely caused more rage than fear and had the effect of motivating rather than discouraging listeners in England. Nonetheless, he was captured by Allied forces at the end of the war, tried for treason in England, convicted and hanged.

I’m indebted to one of our many paid subscribers, Dave Whitman, for mailing me one of the many books by John McPhee, all of which, I suspect, are excellent, although of the 23 listed at the front of “Rising from the Plains,” I’ve read only that one and “The Control of Nature.”

“The Control of Nature” is a collection of a few long essays on a common theme: the transformative power of natural forces like volcanoes and floods and mudslides and the heroic but ultimately ineffective human urge to tame them.

“Rising from the Plains,” the book Dave Whitman sent me, was published in 1986 and is not essays but an entire book on the geology of the west — in particular, Wyoming — and the life and work of the geologist David Love.

I would not be inclined to take down from the shelf a book with “geology” in the title, but even though McPhee descends in detail through the many layers of this subject, he also tells an adventurous and romantic story of one of the few white families to settle in the early 1900s in the remote high country of the state’s center.

McPhee actually tells two stories — one set in the book’s present day (it was published in 1986) with David Love, who gives McPhee a geological tour of the region; and the other about 80 years before, as a young woman who recently graduated from Wellesley College in Massachusetts arrives by stagecoach in Rawlins, Wyoming. The stories soon intertwine.

I’ve been in Wyoming once — driving through on I-80 on my way from one coast to the other — and all I recall is going up and up into country that became gradually more desolate and cold and foreboding. Wyoming is all of that, but much more, too, as “Rising from the Plains” reveals.

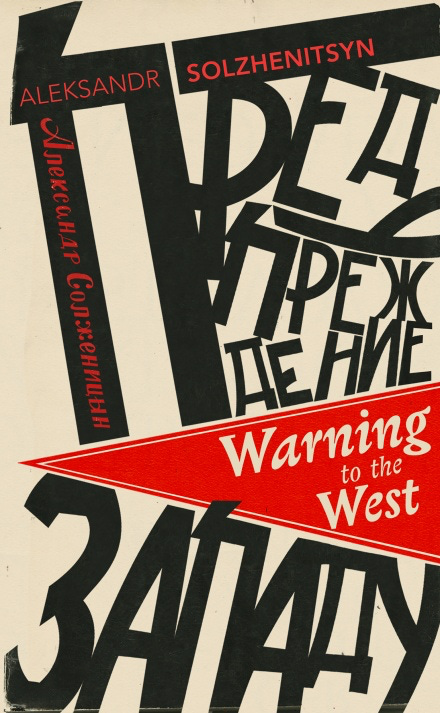

Speaking of foreboding, a couple of months ago, I read “Warning to the West,” a record of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s speeches in the United States in 1975, in which he explores the lies of the Communist party in Russia, starting from the very beginning of the Russian Revolution; its brutal oppression of the people of Russia and other Soviet states; and what Solzhenitsyn condemned as the naivete of the West, especially the United States, and its failure to confront the Soviet threat.

I’m not sure if the reason the Soviet Union disintegrated 14 years later was that it had been a paper tiger all along, or if Solzhenitsyn’s warnings galvanized the west and led to the Soviet collapse. Perhaps both.

I am sure we could use a Solzhenitsyn now. Or, perhaps, we do have one — Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky — but we aren’t listening when he begs us to treat the Russian invasion of Ukraine with the utmost seriousness. We seem to be giving Ukraine just enough help to engage in a war of attrition that, eventually, Russia will win. That would be a tragedy.

Even if his warnings in 1975 were overstated, Solzhenitsyn’s speeches (and his masterwork of investigative journalism — “The Gulag Archipelago”) are bracing, persuasive rejoinders to those in the West who have, at various times, romanticized the communist movement.

“It is a system where for forty years there have not been genuine elections, but simply a comedy, a farce. Thus, a system which has no legislative machinery. It is a system without an independent press; a system without an independent judiciary; where the people have no influence either on external or internal policy; where any thought which is different from the state’s is crushed,” Solzhenitsyn said in 1975.

For those who argue that Stalin and the Soviet bureaucracy betrayed the ideals of the Russian Revolution, Solzhenitsyn reveals that the betrayal took place much earlier.

“… this was March 1918, only four months after the October Revolution, and all the representatives of the Petrograd factories were denouncing the Communists who had deceived them in all their promises. What is more, not only had the Communists abandoned Petrograd to cold and hunger, themselves having fled from Petrograd to Moscow, but they had given orders to open machine-gun fire on the crowds of workers in the factory courtyards who were demanding the election of independent factory committees,” he says.

What astonishes me is to see one of our major political parties, the Republicans, mimic the Bolsheviks’ insistence on falsehoods and tolerance of violence and endorse their “ends justify the means” attitude. To see our country, after decades of defining its foreign and domestic policies by opposition to and contrast with Soviet Communism, now adopting some of the Soviet state’s worst characteristics — that is ironic.

“Warning to the West” is a quick read that contains a lot of cold, hard truth. It is still a warning for us — not so much about Russia now, but ourselves.

Reading, it turns out, doesn’t relieve my political anxieties, but it does give me historical perspective, and reading and writing remain a source of mental relief, more necessary than I could have understood before becoming a caregiver for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease.

It is easy to feel, spending all my time with someone whose mental faculties are fading, that mine are, too. In this situation, clear written expression is like water for my parched mind, and I reach for it many times a day.

Speaking of clear written expression, I was struck by your reference to Rebecca West's phrase in “The New Meaning of Treason,”

"Uniforms were worn that were not really uniforms, that at once claimed and flouted authority, as adolescence does …"

What an apt description of today's Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, and Three Percenters. As members of armed right wing gangs, they wear their costumes to threaten force and disregard norms and institutions. The problem is they're not adolescents, and they're not just playing dress up. They're intent on not abandoning their play-acting as they "stand back and stand by."

Where is a good MAD Magazine when you need one?