Native Americans are not mascots

Losing a little nostalgia is worth it

Nostalgia can take a little hit when school mascot names are changed.

“My kid’s not playing for the Indians like I did. Now she’s playing for the Blue Jays.”

How hard is that to swallow? Can you do it if it means not offending and belittling people? Can you live with losing a mascot that represents a heritage you have no connection to in the first place?

Those are questions that people in Cambridge and elsewhere in New York have to wrestle with, now that New York has prohibited the use of Native American mascots, team names or logos.

Some communities are taking the change gracefully, involving students in the process and using it as a learning opportunity. Others, such as Cambridge, have been forced by a stubborn faction into confrontation, unnecessary legal expense and bitter division.

In Cambridge, the group holding onto the “Indians” name has looked to Dillon Honyoust as a spokesman. An Iroquois Indian who was recently elected to the school board, Honyoust supports the use of “Indians” team names in Cambridge and elsewhere, saying he sees them as positive symbols.

No doubt his feelings are sincere, but the use of him by the district’s anti-change faction is classic tokenism.

“It’s not offensive. The local Indian agrees with us.” — That is their message.

Meanwhile, the nation’s largest Native advocacy organization, the National Congress of American Indians, disagrees with Honyoust and has been campaigning since 1968 against the use of “stereotypes of Native people in popular culture, media and sports.”

Take a look at Cambridge’s old mascot and ask yourself how many American Indians you know who look like that.

Native people were not sealed in amber at the turn of the 20th century. Like Mr. Honyoust, they live in the modern world. They are diverse, and they don’t wear feathers in their hair.

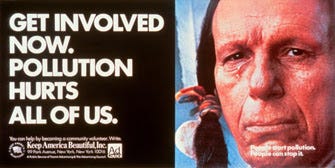

They’re not all men, either — how many times have you seen a female Indian mascot? They don’t all have proud, sculpted visages like the Cambridge “brave,” who happens to resemble Iron Eyes Cody, the Italian-American actor famous for playing American Indians in movies and Keep America Beautiful ads in the early 1970s.

Cody’s pose as a Native American went beyond acting roles. He wore his Native costumes to public events, including one in which he handed President Jimmy Carter a headdress.

Many of us wanted to play the “Indian” and not the “cowboy” when we were kids. But, as a white person, it’s natural to appreciate the wrongness of continuing that as you grow up and learn about the cultural genocide perpetrated by white people against Native people in North America.

Yet the role-playing persists in the use of Native mascots — just ask fans who give war whoops or use the “tomahawk chop” or cheer on an actor dressed in an inauthentic costume, performing an ungainly “war dance” in front of the bleachers.

Defensiveness defines the pro-“Indian” side of the conflict in Cambridge and other places, as people who understand they’re wrong get angry about being told so.

But if you’re willing to learn about the issue, check out the National Congress of American Indians website, which has extensive, thoughtful coverage of it.

Or you can be one of the Washington County white people (hey — new team name?) that shouts about “heritage.”

The heritage that sports fans in Cambridge want to hold onto is a tradition of competition and sportsmanship that won’t go away with the changing of a mascot.

The other heritage represented by use of a Native mascot — the long oppression of Native people and attempted erasure of their culture — is something no one should want to celebrate.

Readings

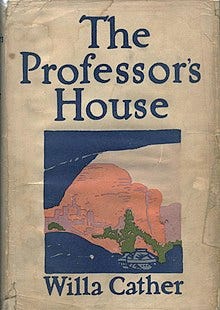

I read Willa Cather’s “The Professor’s House,” another profound novel that convinces me that Cather was the greatest American novelist of the 20th century. I’m no expert; I’ve read only three of Cather’s 12 novels — “My Antonia,” “Death Comes for the Archbishop” and now “The Professor’s House.” But Ernest Hemingway wrote only three good novels — “The Sun Also Rises,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and “A Farewell to Arms” — and I’ve read them, along with a couple of others like “The Old Man and the Sea” and “To Have and Have Not.” None comes close to Cather’s mix of empathetic characterization (of men and women — Hemingway focused almost entirely on men), vivid realization of natural settings and plots that move subtly and effortlessly beyond the interaction of characters to deeper questions of where and how we find meaning in existence.

Hemingway hits the same, sad, macho note over and over, and sometimes, as in the stories “The Three-Day Blow” and “The Killers,” he does it brilliantly. But Cather is always brilliant (from what I’ve seen), her prose is easy and beautiful and her themes emerge naturally from the story she’s telling.

William Faulkner is the other name often mentioned as the greatest American writer of the 20th century, but he’s someone I’ve come to like less and less over the years. I don’t enjoy writing as stylized and obscure as his often is (Toni Morrison is the same way), and there is enough of what seems to be outright racism in his work to make me dislike it. At times, his descriptions of black people fit into the worst stereotypes, and at other times, the way he acts as an apologist for the southern “traditions” of chattel slavery and racial separation and discrimination turn my stomach. I read Willa Cather’s “The Professor’s House,” another profound novel that convinces me that Cather was the greatest American novelist of the 20th century. I’m no expert; I’ve read only three of Cather’s 12 novels — “My Antonia,” “Death Comes for the Archbishop” and now “The Professor’s House.” But Ernest Hemingway wrote only three good novels — “The Sun Also Rises,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls” and “A Farewell to Arms” — and I’ve read them, along with a couple of others like “The Old Man and the Sea” and “To Have and Have Not.” None comes close to Cather’s mix of empathetic characterization (of men and women — Hemingway focused almost entirely on men), vivid realization of natural settings and plots that move subtly and effortlessly beyond the interaction of characters to deeper questions of where and how we find meaning in existence.

Hemingway hits the same, sad, macho note over and over, and sometimes, as in the stories “The Three-Day Blow” and “The Killers,” he does it brilliantly. But Cather is always brilliant (from what I’ve seen), her prose is easy and beautiful and her themes emerge naturally from the story she’s telling.

William Faulkner is the other name often mentioned as the greatest American writer of the 20th century, but he’s someone I’ve come to like less and less over the years. I don’t enjoy writing as stylized and obscure as his often is (Toni Morrison is the same way), and there is enough of what seems to be outright racism in his work to make me dislike it. At times, his descriptions of black people fit into the worst stereotypes, and at other times, the way he acts as an apologist for the southern “traditions” of chattel slavery and racial separation and discrimination turn my stomach.

As someone who went to an all girls high school and had to live with the burden of our mascot being a Panda - and our team nickname being the Nancy Anns ( for Nazareth Academy), all I have to say to those folks bemoaning a mascot name: suck it up.

But seriously,when it comes to team names and statues, etc, in my community, if even a few of my neighbors are really upset by them as being offensive, I'll come down on the side of my neighbors. What's so hard about finding a name we can all live with or a monument we can all tolerate?

OK. But let's not compare Native American names with the silencing of free speech, right and left , we see in colleges. Even Harvard shut down your Congress woman. Let's not expose those fraguile rich kids to points of few that they might disagree with. Lots of times this distinction is blurred. Yet I hate to admit my favorite American author is F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote almost exclusively about rich white Ivy League kids who could not grow up. Oh well !