Early mornings are when I get to be alone.

I wake up at about 4, go downstairs and plug in the percolator, sit on the couch and do a couple of the New York Times word puzzles.

Then I go back upstairs with a cup of coffee and sit at my desk in the little office next to our bedroom and write for an hour or two. I work on these columns and on a longer project, a memoir, I’ve been tapping away at for about two years.

I sit in the chilly little room, glance out the window at the predawn dark and, this morning, think about the prospect that faced early explorers of the Antarctic, such as Apsley Cherry-Garrard, who wrote the book, “The Worst Journey in the World.” I’m trying to cheer myself up.

Before long, I hear Bella stirring in the bedroom and go in to find her pulling on her boots.

“Hi Sweetie,” I say, and I rub her back. “It’s pretty early. It’s only about 5. Do you want to go back to bed?”

“I have to put my boots on,” she says, “but I can’t find them.”

“You have them on, Sweetie,” I say. “But you might want to take them off and get back in bed. It’s still early. It’s dark out.”

“But my —“ she gestures at her feet. “My other things — “ she gestures again.

“Your socks? Your heavy socks? You have them on under your boots. Let’s take your boots off so you can see.”

“No. I have to go to school,“ she says.

“No you don’t,” I say.

“Yes I do. I have to go to school.”

“You’re all grown up now. You’re an adult. Kids go to school, but our kids are all grown up, too. They’ve already graduated and now they’re out working. Right now, they’re sleeping. But when it’s time to get up, they’ll go to work, because they’re adults. You graduated a long time ago. Remember how you used to go into Mr. Dixon the principal’s office and smoke cigarettes with him? And when you graduated he picked you up and twirled you around? Remember? And he said, ‘I’m so glad you’re leaving!’”

“Yes,” she says and smiles.

Then she tugs at her boots.

“I need to get to school,” she says.

We go downstairs and put on our jackets and hats and mittens and walk out to the car with Ringo and drive over to Quade Street and park. The schoolyard is empty, the entranceway lit up brightly. It’s dark where we sit on the far side of the street in the only car on the street.

“No one’s here,” I say. “It’s too early.”

Bella’s eyes are wide. She looks scared.

“We can walk up to the front door if you want,” I say. “We can’t go in, because it’s locked. But we can walk up and look in. Do you want to do that?”

“No,” she says.

“Should we go home?”

“Yes,” she says.

At home, we sit at the butcher block in the kitchen, and I pour Bella a cup of coffee and put some toast in the toaster.

“Do you want some coffee?” she says.

“I’ve got some,” I say, pointing to the cup I left behind when we went out.

“Isn’t it nice to be home?” she says.

We munch on toast and sip our coffee, then she stands up with a smile.

“It’s time for bed,” she says.

“Yes it is,” I say.

“Are you coming to bed with me?”

“I’ll get in bed and read my book while you sleep,” I say.

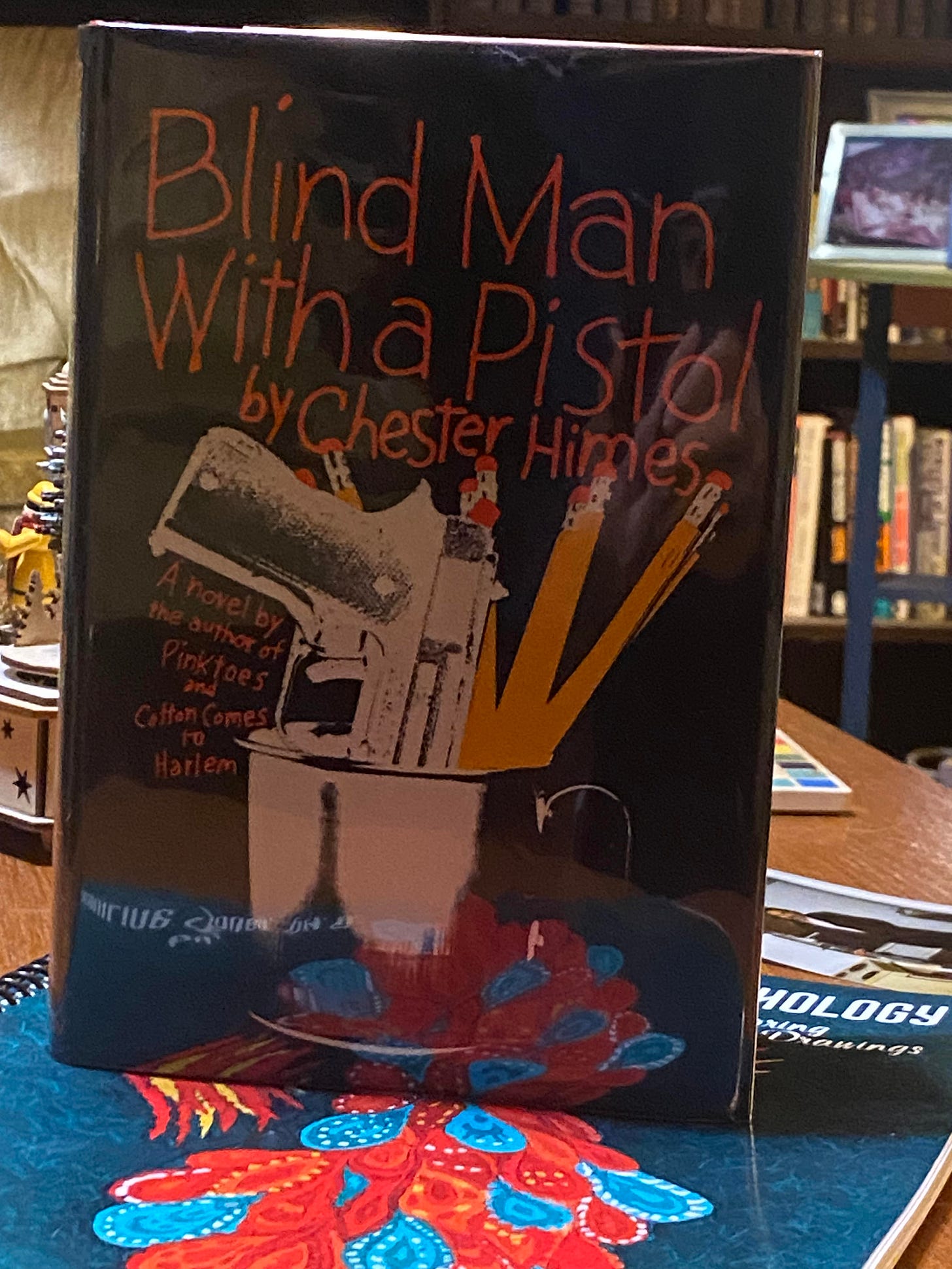

I’m reading “Blind Man With a Pistol,” written in 1969 by Chester Himes. It’s the final novel in his Harlem Cycle, featuring graphic descriptions of blood and sweat on naked bodies, living and dead.

Bella falls asleep quickly, and after 15 or 20 minutes, I tiptoe out, back to my office. Ringo needs his anti-seizure pills before 8, and I don’t want Bella to sleep too late. In the meantime, I can wander a little further through this morning’s unwritten world.

‘Blind Man With a Pistol’

It’s hard to beat the title of Chester Himes’ 1969 novel, the eighth and final book in his Harlem Cycle but the first one I’ve read. The title may be meant as a metaphor, but it is not just that, as, throughout this novel, strange and disturbing situations play out on the page. The settings and the action have a surreal quality, the writing is flamboyant and odd and frequently hard to follow, the dialogue is contrived, but the whole creation is so vital and energetic and, in its moments, compelling and upsetting, that it works.

I won’t bother with a plot summary, because I can’t come up with one. Murders occur, but I can’t remember how many. Do the two Harlem detectives, nominally the protagonists, solve any of the cases? I’m not sure.

But I’m glad I read the book, and I intend to read at least a couple more of the Harlem Cycle. Himes took me on a tour of an unfamiliar place, and despite how unsettling the experience was, the startling gusto of his writing makes me want to go back.

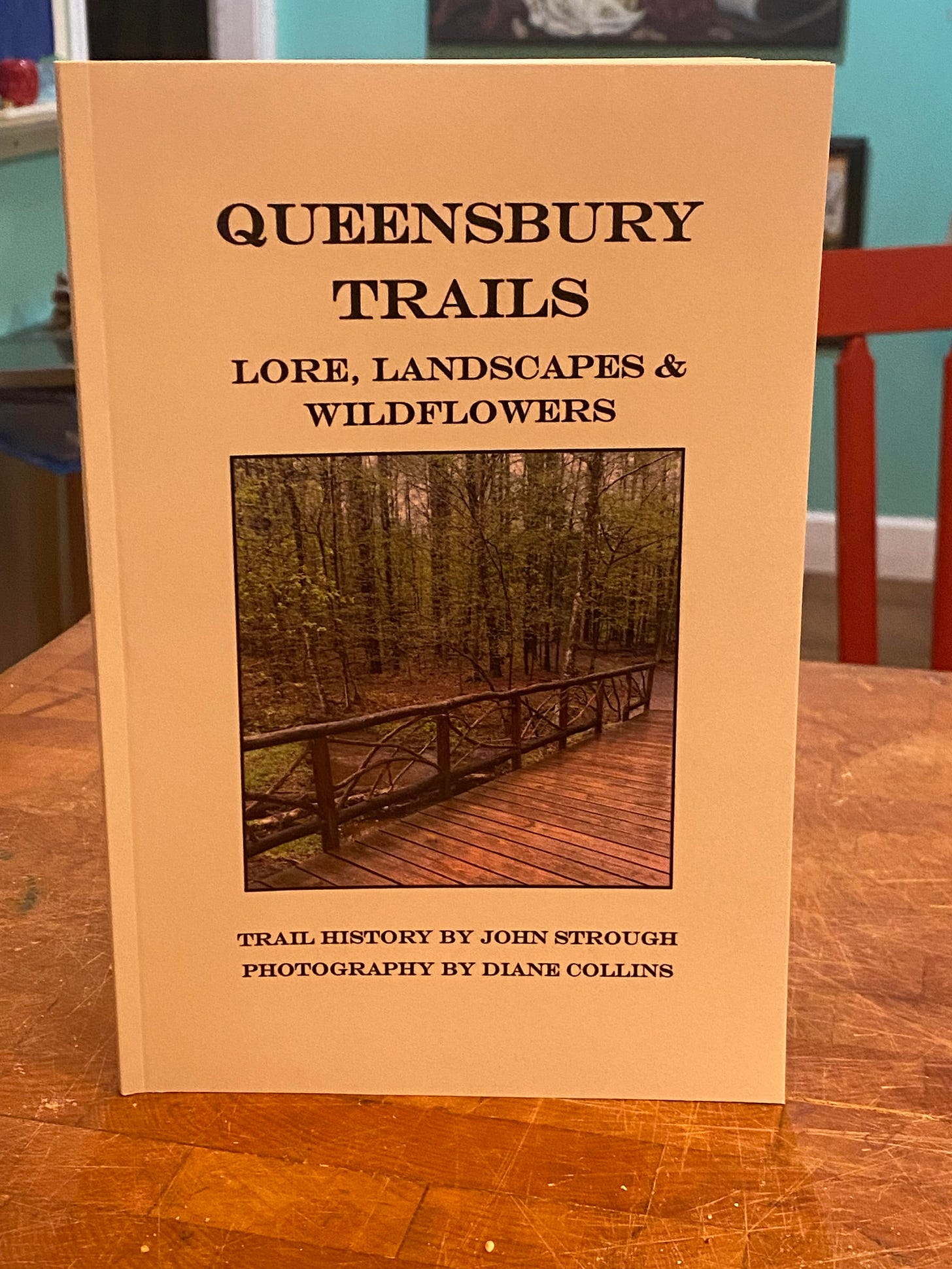

Trail book trilogy

Diane Collins of Glens Falls has published a third book in her trilogy on local trails, this one with brief texts on trail history by John Strough, Queensbury town supervisor and trail enthusiast. Like her other two, on Cole’s Woods and the Betar Byway, it’s a lovely little book, filled with scenic photos and shots of carefully identified wildflowers.

This book, “Queensbury Trails: Lore, Landscapes & Wildflowers,” focuses on five trail systems in town: Rush Pond, Halfway Brook, Meadowbrook Preserve, Gurney Lane and Hudson Pointe Nature Preserve.

The book is published by Warren History Press of the Warren County Historical Society, funded by a grant from the Touba Family Foundation, and is available locally.

Thank you, Will, for sharing stories of your journey with Bella. The love you have for each other is magical. I'm certain she knows this viscerally, though she gets the setting wrong. Love and kindness bring as much to the giver as to the receiver.

The love, patience, and respect you have for your wife are outstanding. I know how hard it is to care for someone with Alzheimer's. She is very lucky to have you.