Book captures feel of region and local journalism

Prison closures are a good thing

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

I used to walk around, 30 or more years ago, with a paperback book in my pocket, so I’d have something to do when I was waiting in line or in an airport or a doctor’s waiting room.

Now everyone, including me, does that with their phones. I wonder if literacy has increased because of all the extra hours we spend reading now.

We also write more than we used to, in texts and emails and posts on social media. It might not be good writing, but it’s communication through the written word.

Amid all the bemoaning of the awful effects of smartphone use on our attention span and ability to spell and communicate face to face, it’s worth acknowledging that we are writing more than we used to, not to mention learning to type with our thumbs. Some of us also are becoming fluent in a new language of abbreviations, contractions, creative punctuation and emojis — phonish?

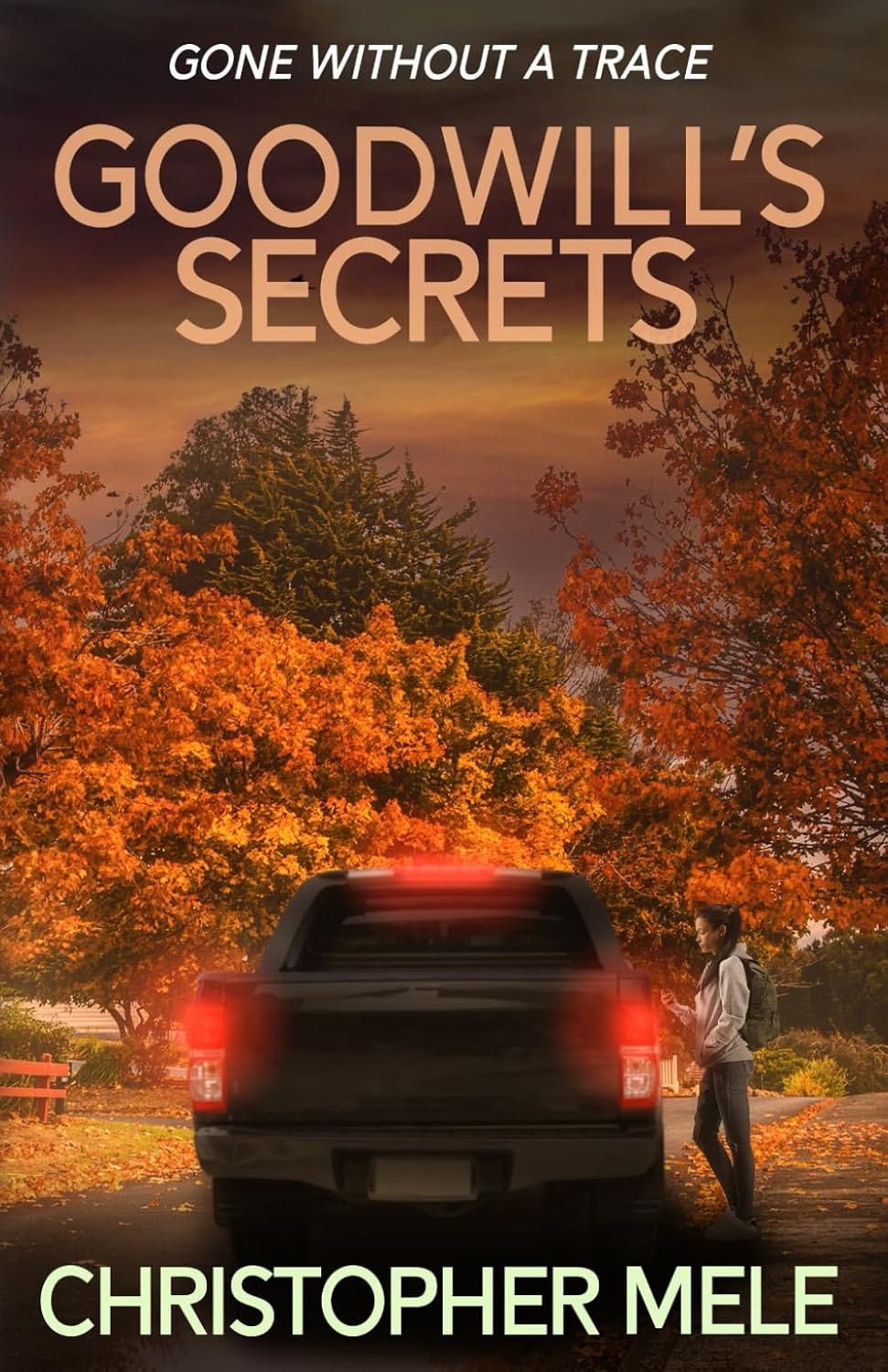

Chris Mele, a journalist who now works at the New York Times as an editor on the breaking news desk, has written a book perfect for pulling out of your back pocket while you wait in the coffee shop line. It’s called “Goodwill’s Secrets” and is set in northern New York, in a mountain village somewhere very close to Saranac Lake, where Chris lived for a few years while working as a reporter at the Adirondack Daily Enterprise.

My father, Bill Doolittle, was, at that time, the publisher and editor of the Enterprise, and Chris and I got to know each other. Regardless of our personal connection, I’m glad I read his book, because it moves along briskly and unpredictably and approaches the conventions of the genre in an uncommonly grounded, realistic way.

The action doesn’t take place over a frantic few days, following a protagonist who never seems to sleep or eat. It plays out over nearly a year, as Alex Provetto, an accomplished middle-aged reporter who has been exiled to the Adirondacks, is repeatedly drawn back to the story of a missing teenage girl.

Provetto is dogged and resourceful but not extraordinarily perceptive or tough — the “bad guy” eventually finds him, not vice-versa, and he doesn’t knock anyone out. The pleasure of the book is in the details of the reporting process — the missteps and the lucky breaks, the negotiation with sources, the persistent gathering of information that seems to lead nowhere.

I talked with Mele by phone for about an hour on Wednesday, and here is an edited version of our chat:

Your plot isn’t compressed as in a lot of murder-mysteries. It takes place along a realistic timeline.

“I’ve heard that before, and it’s vitally important to me. I call it ‘fictional realism.’ I wanted the book to be very much grounded in reality.

“Alex is a bit of an educational tool to show the reader what is involved in reporting. There’s nothing straight line in reporting. It can be very meandering. It can be very plodding.

“‘Slow the action down’ became a bit of a mantra for me. In journalism, you have 15 inches, 500 words. You’ve gotta hold the reader’s attention.”

Alex isn’t superhuman. He’s very relatable.

“I’ve heard that before, and it wasn’t necessarily foremost in my mind. He’s somebody that’s got a lot of ‘Marlboro miles’ on them — war-weary and beaten-down, he’s got scars, that sort of thing.

“I wanted Alex to be a composite of reporters I’ve worked with.”

The novel takes place in the real world in a village that seems to be close to Saranac Lake. Why didn’t you just call it Saranac Lake?

“I liked the name Goodwill.” (He explained that he liked the contrast between the connotations of the name and the ugly secrets hidden beneath the surface in the fictional village. Also, he wanted to keep the book “realistic” but didn’t want to distract himself or readers with checking whether actual details, like the names and layout of the village streets, matched the book.)

Also, he said, “I wanted to be a little bit careful about people reading into it.”

Was it painful to kill off your victims?

“I saw it as a necessary evil. It was a key plot consideration, and I was kind of ruthless about it. It’s a corollary with ‘kill your darlings’ (the advice given to reporters to remove their favorite bits of writing from stories if they’re not relevant).

Are you working on a follow-up?

“I am. I can’t stop myself. I haven’t done any writing, but I’ve done a lot of thinking and note-taking. I’ve written about 300 emails to myself.

“So much of writing is problem-solving, like a Rubik’s cube. Probably in November I’ll start writing in earnest.

“I spent about two and a half years writing (on “Goodwill’s Secrets”).

“I thought the writing was challenging, but the marketing and promotion is so much harder. It’s time-consuming and also psychically taxing, because I’m not a sales guy. I’m not a guy who, in the parlance of the day, has ‘built his brand.’ I am sort of allergic to it.”

Not bad

A Washington County report has told local officials what they already know: Closing Great Meadow state prison will hurt the local economy.

How much it will hurt and for how long the report can’t say, because no one knows how many workers will accept transfers to prisons elsewhere in the state, how many will be able to transfer to the neighboring prison, Comstock, or to local county jails (eight have already been hired by Warren County) and how many will find other jobs nearby.

Since prison jobs pay well, it is possible that quite a few of the more than 600 people being laid off will accept transfers.

But what is the alternative to closing prisons at a time when the state inmate population is falling fast, and the state is struggling to fill open positions at prisons?

Prisons are notoriously expensive to operate. New York is saving $442 million a year because, as the prison population has declined by 55 percent over the past 15 years, 24 prisons have been closed.

Although local politicians like Dan Stec and Matt Simpson are shouting about Great Meadow, what do they suggest? They also like to shout about the high taxes in New York. Should the state keep half-empty prisons open so taxpayers can subsidize jobs that are no longer needed?

In the long run, Washington County and everywhere else will do better if the state runs an efficient Department of Corrections, maintaining only the prisons it needs for the inmate population it has.

The cries of alarm over Great Meadow will not prove justified. Some of the employees will retire, taking their pensions and, perhaps, starting small businesses, and some will find other jobs in the area. Some, but nowhere near all, will leave. It will be difficult, but the predictions of huge sales tax declines, devastating school enrollment drops and the loss of hundreds of other jobs because of a lack of customers will not come true.

One of the unfortunate defining characteristics of the United States is its high rate of incarceration. We imprison a lot of people compared with other industrialized nations, both because we have more crime — especially gun crimes — and we favor long prison sentences.

But serious crimes are way down in New York over the past 25 years, and we are no longer locking up thousands of young men for minor, nonviolent drug offenses.

Yes, it is hard for employees’ families and the communities where they live when prisons close. But from the perspective of the health of our state and our nation, a reduction in our incarceration numbers, reflected in the closing of prisons, is a purely positive development.

Oktoberfest

Bella and I were at our perch in front of Spot Coffee Saturday as the city’s first Oktoberfest got underway. It looked and sounded great, and we grabbed a delicious bratwurst with sauerkraut from Radici on our way by their booth.

Thanks, Will, for your fresh perspective and insights on the prison closings. I hope your analysis proves true and the outcomes you envision are realized. In the meantime, we need to be sensitive and vigilant in our caring for those caught up in the transition.

It seems like socialism to keep a prison open unnecessarily only to provide jobs. Stec, Simpson and Stefanik aren’t in favor of socialism are they? It doesn’t make economic sense, in any case.