Adirondack book illuminates 'the Black Woods'

Trump's outrages aren't 'Kafkaesque,' they're Hitler Lite

Please consider supporting The Front Page with a paid subscription: HERE

Amy Godine is an independent researcher and scholar who lives in Saratoga Springs and likes to point out connections many people would prefer to ignore.

In 2015, she wrote a piece for Adirondack Life, “Conservation’s Dark Side,” that explored the historical tie between eugenics and the conservation movement, nationwide and in the Adirondacks.

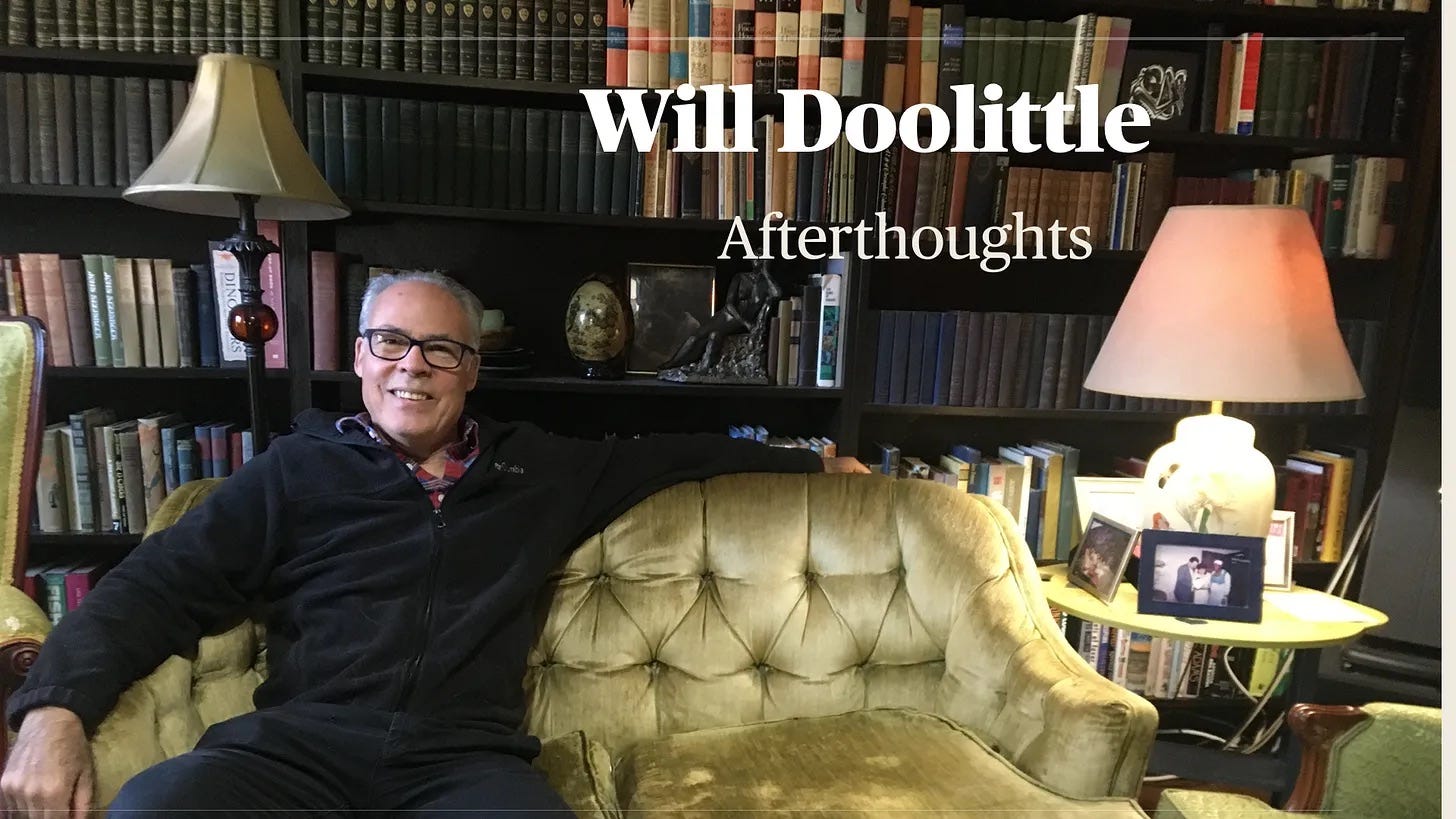

In 2023, Cornell University Press published the book she had been working on for a couple of decades, “The Black Woods: Pursuing Racial Justice on the Adirondack Frontier.” The book is about a resettlement project launched in 1846 by a wealthy, white abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, to give Black people from around New York land in the Adirondacks to farm. It was an unconventional choice of subject, since Smith’s project, at least as he conceived of it, was largely a failure.

Smith had inherited huge swaths of land in the North Country, and he gifted plots of 40 acres each to 3,000 Black individuals and families. The idea was to help the grantees become self-supporting and, thereby, free of the smothering racism of the time, and to provide them with a path to suffrage.

Slavery had ended in New York in the 1820s, but Black citizens were required to own land worth at least $250 before they could vote. Smith’s plots of unimproved land were not worth that, but with time and work, they could be.

The number of grantees who moved to their properties numbered in the dozens, not in the thousands, and some moved away after a few years. The project left no mark on the lands where it was sited, and little historical notice has been paid to it, until now.

Godine makes much out of what looks like scant material. Her prodigious, painstaking research sets the Smith land giveaway in the broader cultural context of the fraught decade preceding the Civil War, as Black citizens in the North — not enslaved but not free of racist oppression, either — sought to find a place for themselves in the world.

She follows the lives of Black grantees from years before they went to the Adirondacks and for years afterward. She delves into the circumstances of agents who found land grant candidates for Smith but weren’t interested in resettlement themselves, because they already had full, prosperous lives elsewhere. She points out that upstanding citizens were recruited for the project from cities like Troy and Albany, although they had no experience as farmers and were being given no outside support — no startup capital, no equipment to work the land.

The surprise is not that the goal to establish hundreds of working Adirondack farms wasn’t reached but that anyone succeeded at it.

What is not surprising is that the failures of this half-baked scheme was laid at the feet of the Black grantees, not the rich white man who conceived it.

“The big surprise is how interesting and important the story of the after-story was,” Godine said — “how it was rewritten to accommodate ideas about race and who belonged in the area and who didn’t; how the history got repurposed and trimmed to fit another kind of agenda. That really lit my fire.”

The narrative that emerged over time was that the grantees were unsuited to farm work, that they were not capable. Smith’s grand experiment floundered, this story said, because the Adirondacks was a hard place to thrive — too cold, too isolated — and only hardy white folks were up to it.

What is impressive under the circumstances is how varied and accomplished the lives were of grantees who went to the Adirondacks and also of those who decided not to go north. Godine shows us both in great detail.

“The Black Woods” contains a lot — a lot of names, a lot of facts and a lot of anecdotes — but all of it helps to tell the real story of the Black Woods and reveal the depth and variety of the lives of Black residents of the Northeast in the pre-Civil War era.

The story doesn’t sink under the weight of its detail, it rides on it, and it carries you along.

More reading

I picked up “The Trial,” written by Franz Kafka in 1914 and 1915 but published n 1924, after his death, because I saw a remark from the lawyer for Kilmar Abrego Garcia, calling his wrongful deportation to a brutal prison in El Salvador “Kafkaesque.”

“The Trial” concerns Joseph K., a bank official, who seems to slip into a bizarre, surreal existence after a couple of men knock on his door to inform him he’s under arrest.

I’m near the end of “The Trial,” and based on this novel, I wouldn’t call Garcia’s arrest and imprisonment “Kafkaesque.” I’d call it horrible, wrong, appalling and cruel. But what happens to Joseph K. is far more ambivalent, confusing and internal than what has happened to Abrego Garcia.

The treatment of Abrego Garcia is fascistic, the operation of an abusive police state by a fascist wannabe. The current foot-dragging by the Trump administration, flouting a court order to bring Abrego Garcia back to the U.S., is a declaration of its character and intent. Trump believes he can act with impunity, that he has power over our bodies and can punish us, even erase us as Abrego Garcia has been erased, for what we think and say.

Nothing about the abduction of a man in the country legally and his transfer to a foreign prison known for torture of inmates is ambivalent or surreal. It is all too clear what has happened, and for Abrego Garcia and his wife and three children still in the U.S., it is all too real.

Caregiving is Kafkaesque

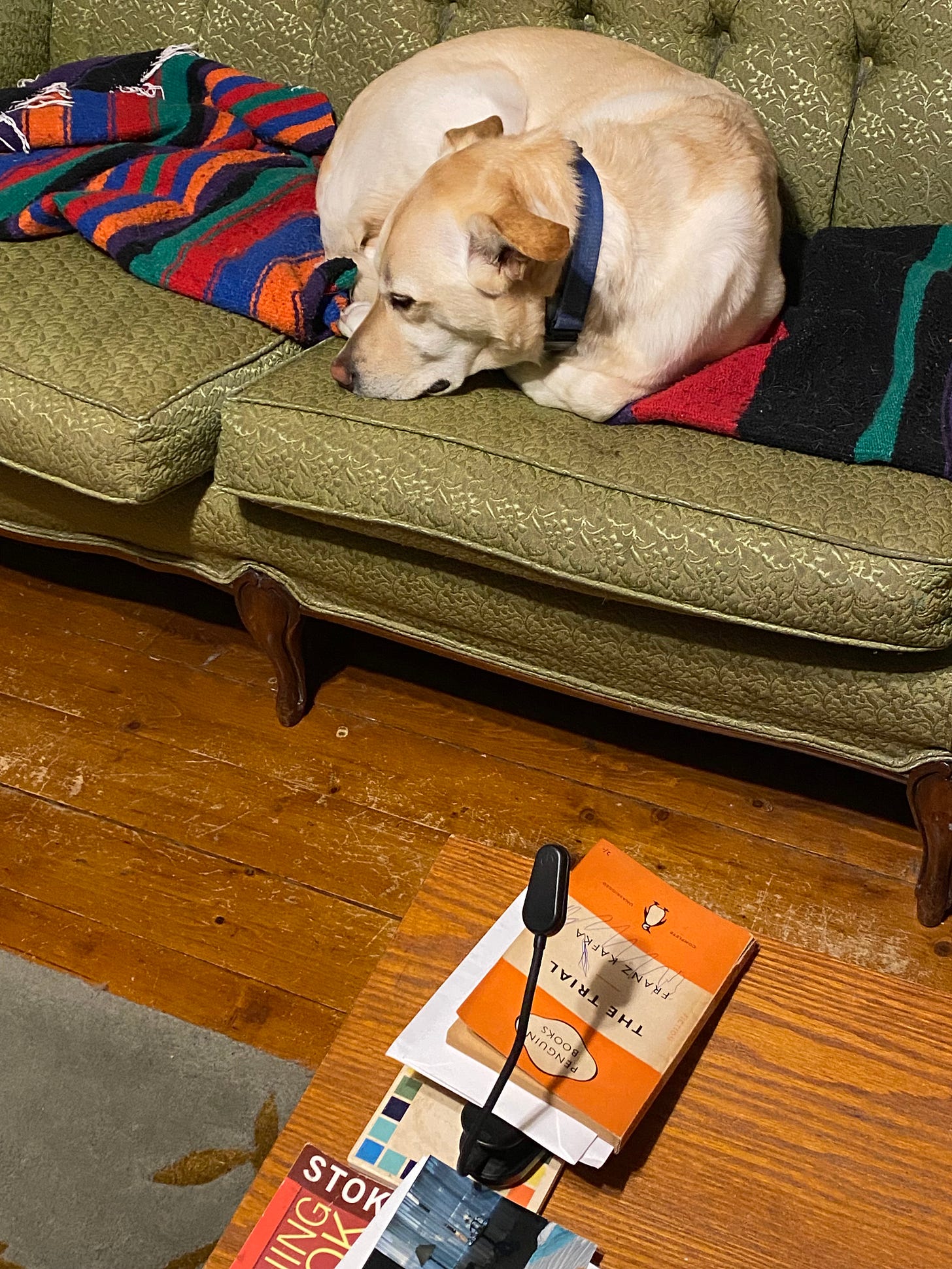

Being the full-time caregiver for someone who has Alzheimer’s does often feel surreal. The experience is full of confusion and ambivalence and emotional whipsawing — listening to your spouse open and shut the front door 15 or 20 times over the course of an hour to call the dog, who is curled on the couch; taking her to bed because she has said she’s sleepy and covering her up, only to have her throw the blankets back and walk, muttering, into the kitchen; having her hold your hand while you’re driving but pull it away in anger and refuse to get out of the car when you reach the coffeehouse where she said she wanted to go.

Caregiving combines boredom, anxiety and frustration in an extraordinary way that I find Kafkaesque.

Thank you for highlighting and recommending Amy Godine's book, The Black Forest, and the failed, misquided experiment by abolitionist Garrett Smith. Timbucktu has been heralded of late as something to admire rather than point out the lack of support and the isolation (separate and not quite equal). This administration's racist, political persecution, anti-democratic and empirical designs are not fascist lite. They are fascist. Your experiences as a caregiver test the mind and body to the extreme. Please forgive my concerned opinion that you cannot do it alone.

Will

I admire your commitment and courage as a caretaker/giver. Hope I could do it if ever called upon. In my prayers.